President Trump thanks Andrew Wheeler, EPA Administrator, after Wheeler delivers his speech on America’s environmental leadership Monday, July 8, 2019

By Chris Sellers, Marianne Sullivan, Kelsey Breseman, Eric Nost, and EDGI

Executive Summary

Over the past three and a half years, the Trump administration has engaged in a historically unprecedented campaign to shrink our government’s capacity for reliable, professionally vetted environmental knowledge. The most draconian statements of its vision have come in its annual proposals for budget cuts. Though these cuts have been repeatedly rejected by Congress, Trump political appointees have succeeded in significantly shrinking resources and personnel devoted to environmental sciences within the executive branch. This downsizing, done by means outside of Congressional control and underneath judicial and media radars, has left deep and debilitating scars on the scope and capabilities of federal environmental science, which will likely take years to repair. Our diminished capacity to understand the environments that surround us has corroded our government’s ability to protect our nation’s ecology and public health, leaving both more vulnerable.

Our report highlights:

- Some common threads in the Administration’s efforts to cut the capacity of environmental science across the Executive branch:

- Depicting environmental science and scientists as pitted against business profits, jobs, and the economy

- Establishing the idea that there are “core” government functions, separable from those that are more “peripheral” and “expendable”, and invoking that boundary to pare back environmental research

- Targeting especially those federal agencies and offices where environmental science has been effectively integrated with environmental policy-making

- How the administration has curbed the voice and presence of environmental science starting at the top, within the White House:

- The National Security Council lost expertise on global health security and medical preparedness, while gaining the retired physicist William Happer, a critic of climate science

- The Office of Science and Technology Policy, after being headed by the environmental scientist John Holdren under Obama, went leaderless for two years and shrunk by nearly two-thirds. Then under Kelvin Droegemeier it has pursued a studiously apolitical and business-servicing agenda

- The Council on Environmental Quality also went without an appointed leader for the first two years. Then under Mary Neumayr it has focused mainly on “streamlining” its “core” responsibility, the National Environmental Policy Act, among other ways by requiring fewer scientific studies or questions

- Evidence of special animus toward environmental sciences, especially when closely tied to environmental policy-making, as shown through proposed budgets as well as actual reductions in resources and staff over the last three years:

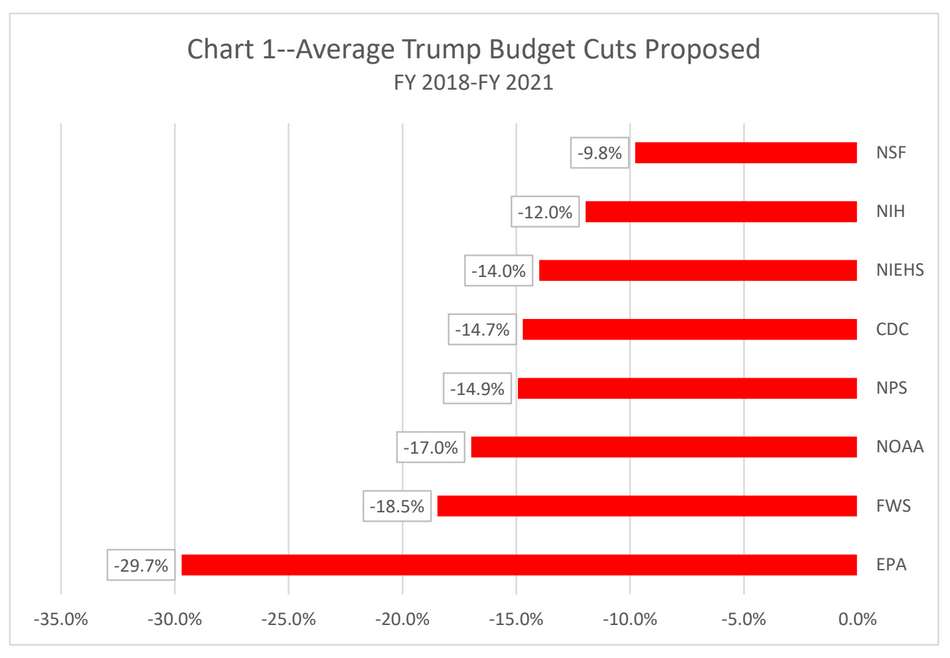

- Proposed cuts to NSF and NIH were relatively modest, averaging 9.8% and 12%

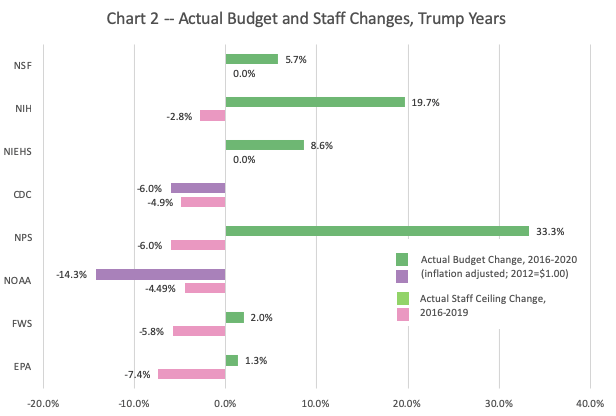

- Congress, by contrast, raised the NSF budget by 5.75% and that of the NIH by 19.% between 2016 and 2019

- Staff remained level (NSF) or dropped slightly (NIH, by 2.8%) over this time.

- Proposed as well as actual cuts to environmental and public health science-dependent agencies were significantly larger

- Proposed budgets over four years for the CDC, the NIEHS, the NPS, NOAA, and the FWS ranged between 14% and 18.5%. EPA’s proposed cuts, however, surpassed all these others, averaging 29.7% over the four years

- With the notable exceptions of NOAA (which lost 14.3% of its budget), and the CDC (which lost 6%), Congress sustained the budgets of most of these agencies at slightly higher than previous years

- However, unlike the NSF or NIH, most of these agencies have seen significant losses of staff, between 4.5% and 6%

- The greatest loss of personnel, 7.4%, has come at the agency also most targeted by Trump budget cuts, the EPA

- Within agencies such as EPA and NOAA, scientific research divisions were among the most targeted by Trump budget cuts, and also among the hardest hit by actual reductions in resources and staff between 2016 and 2019

- In the EPA, these research oriented offices have endured more severe actual budget cuts and staff reductions than in NOAA

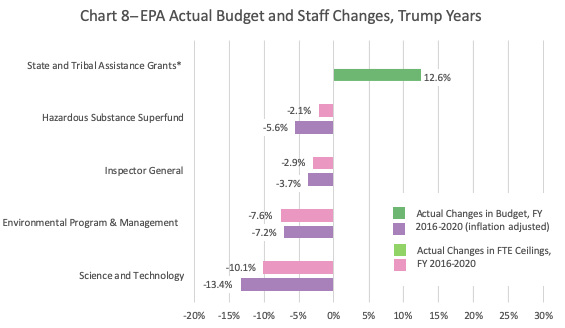

- EPA over the Trump years has lost 13.4% of its budget and 10% of its staff working on science or technology

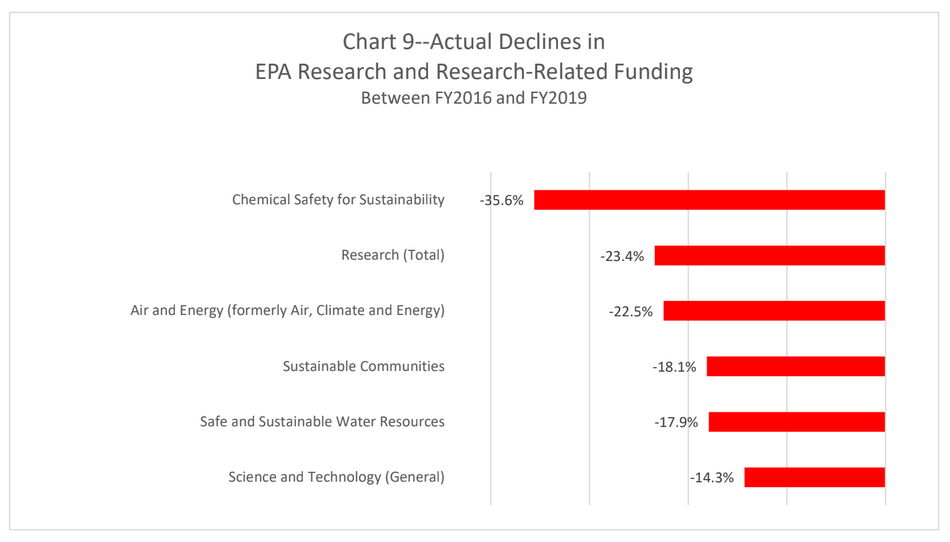

- EPA’s budget designated for research has plunged by 23.4% overall. The 35.6% reduction in funds for studying “chemical safety for sustainability” has even surpassed the 22.5% drop in money for researching “air and energy” (formerly termed “air, climate and energy”)

- Proposed cuts to NSF and NIH were relatively modest, averaging 9.8% and 12%

- A dissection of the decrease in EPA’s staff:

- Overall, it is down by 21.7% in 2019 from its peak in 1999, bringing it to a level last seen during the Reagan administration of the 1980s.

- Between a third and half of this two-decade decline has come during the Trump years, between 2016 and 2019. While the agency reports a 7.6% decline in Full-Time Equivalents over these years, FOIA’d staff lists indicate a 12.2% decline in “on-board” (currently on salary whether full- or part-time) personnel

- Few EPA employees have been fired. Instead, the political leadership has accomplished staff reductions through ongoing normal attrition of the agency’s older workforce, prodded by an early buyout and its sometimes neglectful or disdainful treatment of career staff, combined with what seems a strategic reluctance to replace departed staff, whether through hiring freezes or slowdowns

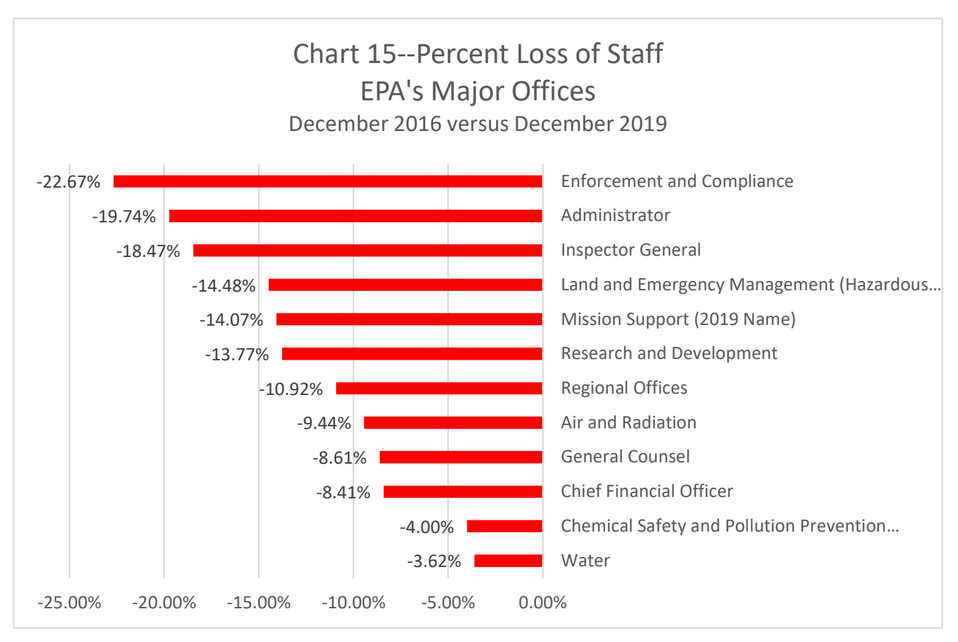

- Among the hardest hit of offices:

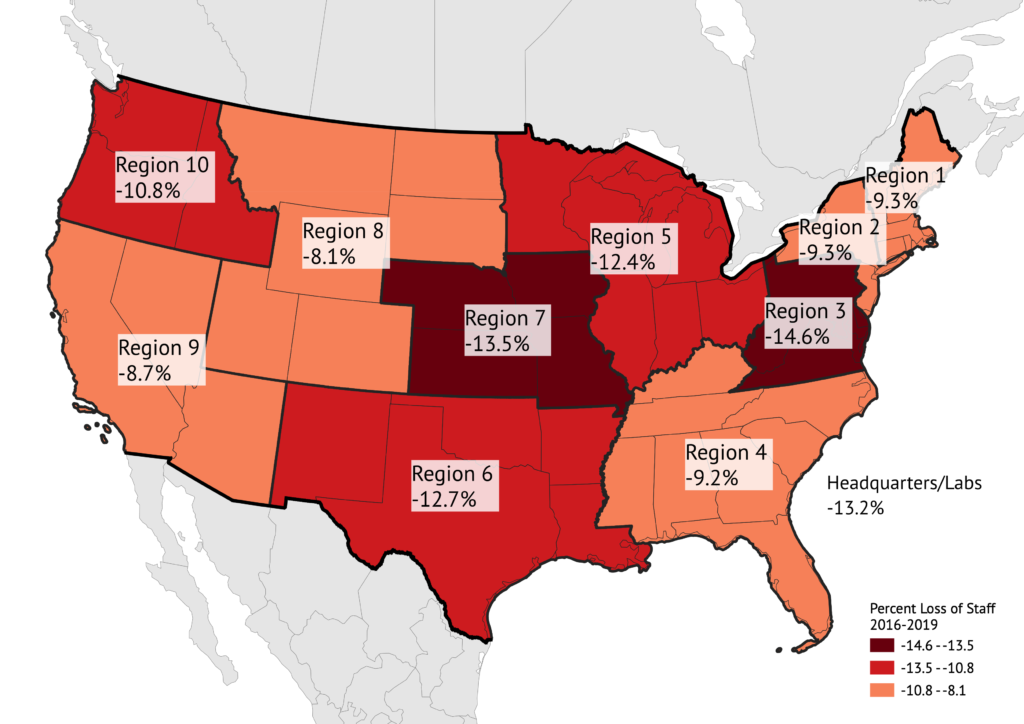

- Region 7 (-13.5%) and Region 3 (-14.2%)

- Headquarters and Labs–(-13.2%)

- Enforcement and Compliance (-22.6%)

- Administrator’s Office (-19.7%)

- Inspector General (-18.5%)

- Research and Development (-13.8%)

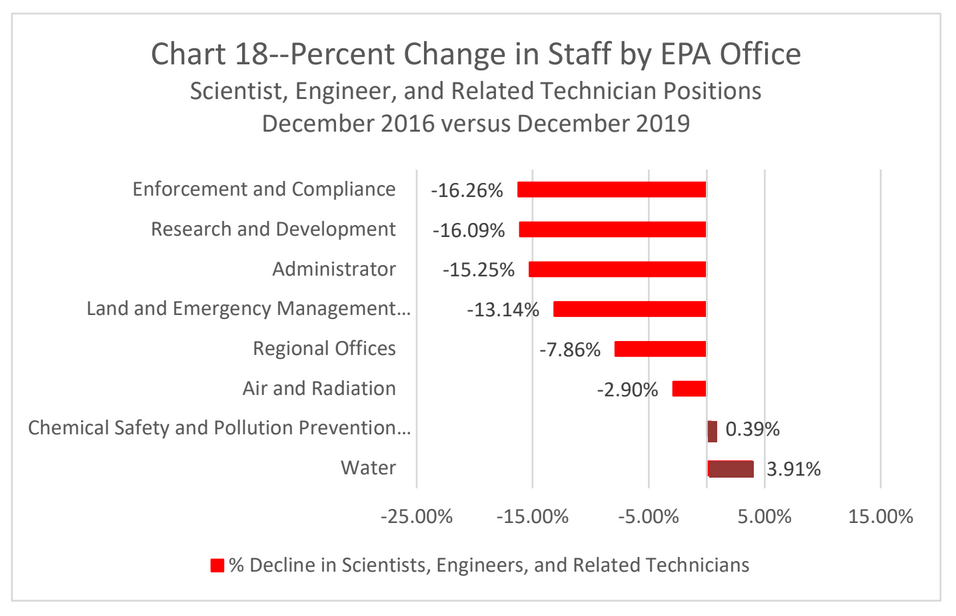

- Among the offices losing the most scientists, engineers, and related technicians:

- Enforcement and Compliance (-16.3%)

- Research and Development (-16%)

- Administrator’s Office (-15.3%)

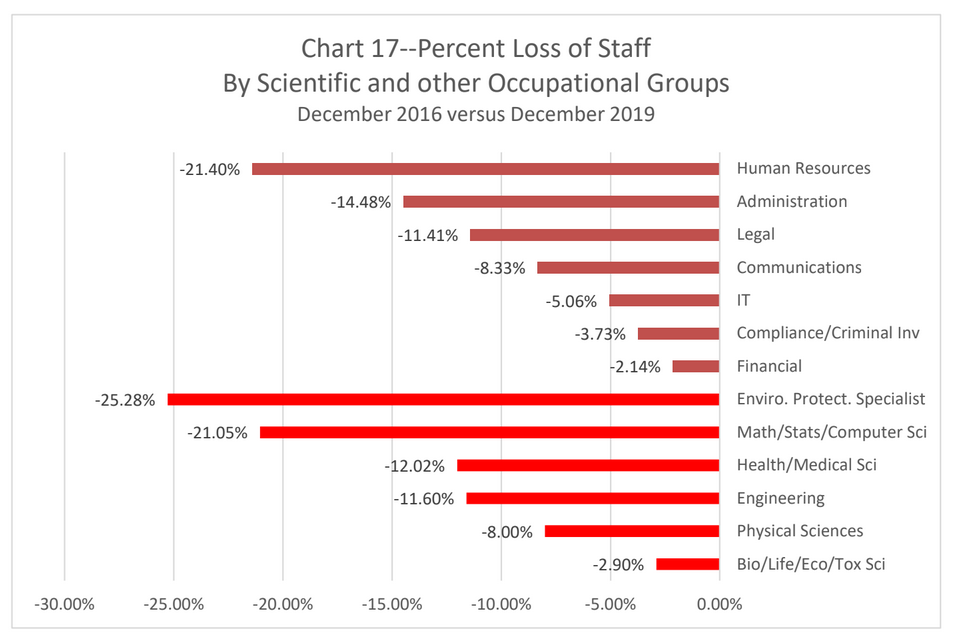

- Among the hardest hit of scientific occupational groups:

- Environmental Protection Specialists (-25.8%)

- Math, Statistics, and Computer Scientists (-21.1%)

- Engineering (-11.6%)

- Physical Sciences (-8%)

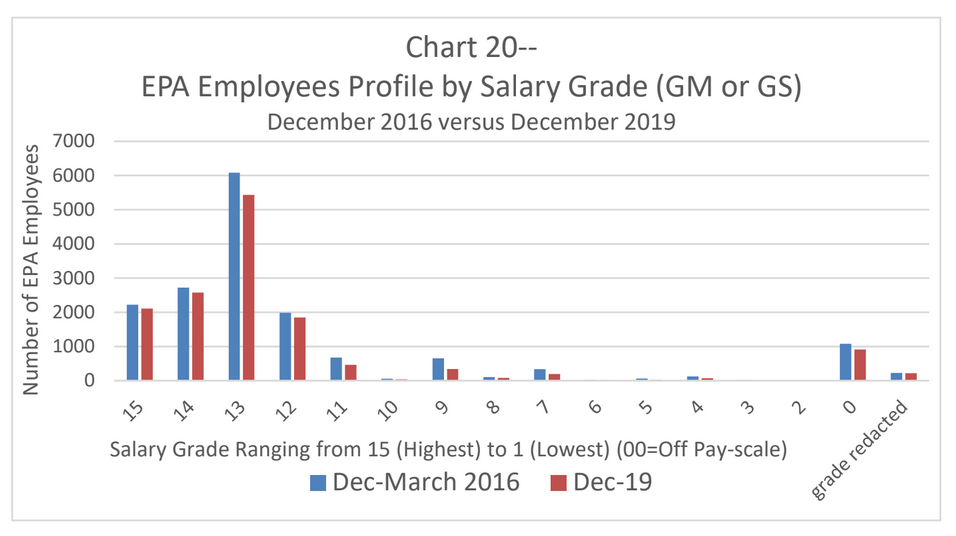

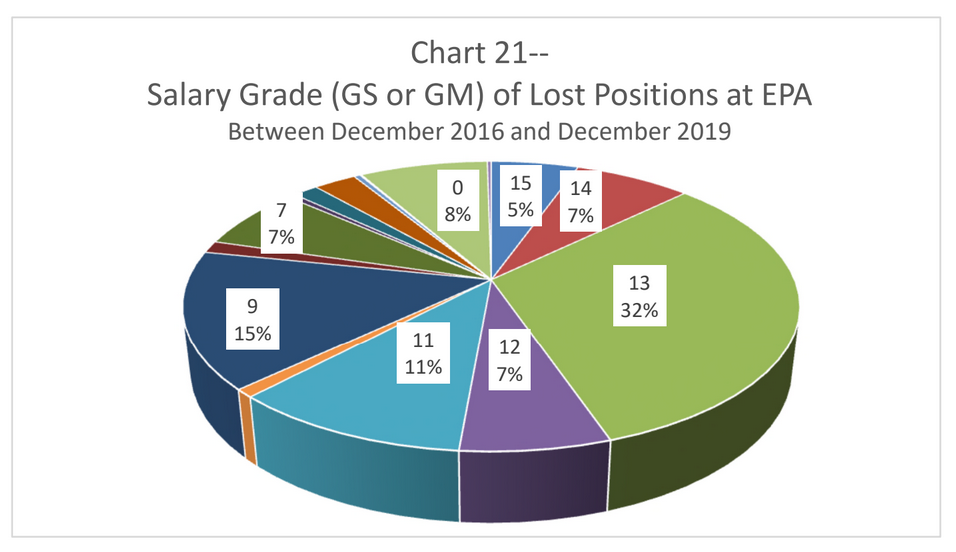

- The greatest share of lost positions between 2016 and 2019 came at senior levels. The GS 13 (out of 15) grade comprised 32% of the losses, and 44% of them came at levels of GS 13 or higher

- Analysis of the disproportionate loss of the EPA’s older and most experienced personnel. Taking with them not just scientific knowledge but a wealth of other know-how with them, their departures have corroded the ability of remaining staff to:

- Navigate the bureaucracy

- Work with other staff in different fields on common problems

- Collaborate with other agencies and outside stakeholders

- Accomplish all of their assigned tasks well; shrinking offices and teams are forced to make their own decisions about what activities they can and should sustain

Overall, the EPA’s reductions in capacity are making it less able to handle environmental problems both old and new. As with the Trump designs for the CDC prior to COVID, the nation’s premiere environmental regulator is being remade into an agency that is more static and reactive. Losing scientific “eyes” alongside its enforcement “teeth,” the EPA is being shorn of its power to anticipate or prevent, leaving Americans increasingly defenseless against a host of environmental threats.

Introduction

Trump and his appointees have undertaken a historically unprecedented campaign to shrink our federal government’s capacity for reliable, professionally vetted knowledge. This devaluation of science has most deeply affected what we can know and do about the environments that surround us, which deeply affect our nation’s ecology and public health. We continue to learn more about just how the Trump administration has underprepared us for the current pandemic, but its shearing of our public health science and capacity comprises only a single facet of a more sweeping three-and-a-half-year assault on federal environment science. Since arriving in Washington in the early weeks of 2017, Trump-appointed regulators have striven not just to curb the influence of science on environmental policy but to downsize federal agencies that undertake or support environmental and public health science.

White House-proposed cuts to federal environmental and public health science over the last four years easily comprise the most high-level and ambitious offensive of the past half-century against the knowledge-making machinery on which our modern environmental laws rest. Even before the House turned Democratic in 2018, however, the two houses of Congress have balked at the extent of White House-proposed cuts. Though frustrated by Congress in its most radical budget-slashing plans, the Trump administration has nevertheless already left deep and debilitating scars on the scope and capabilities of federal environmental science, which will likely take years to repair.

Blocked by Congress, the Trump administration has found other ways of whittling down the scientific infrastructure of labs, research programs, and expert personnel on which environmental agencies depend to protect our health and ecology. Denigrating, reprioritizing and reshuffling the responsibilities of many agency staff, prodding attrition while putting brakes on new hires, Trump environmental appointees have shared a common strategy with the reliably draconian budget proposals emanating from the White House itself. Paring back agencies to those fewer functions they deem “core,” they treat all other existing work of their agencies–in particular policy-relevant environmental research–as less important and in many cases, simply expendable. This study assesses how much federal environmental science has suffered from this and other methods for demoting it across the executive branch over the last three years: how much it has lost not just in influence but in resources and human capacity.

We find that, in the face of steady Congressional opposition, the administration has indeed been able to shrink entire agencies and offices. Unlike its policy rollbacks, these changes have also escaped the scrutiny of the courts; nor has a media preoccupied with the COVID-19 paid much attention. Over the past three and a half years, working largely in shadows, the administration has substantially curtailed the scope and capabilities of environmental science within our federal government. The reductions have gone furthest precisely in those agencies and offices where knowledge-making and expertise are most closely connected to the implementation and enforcement of our environmental laws.

To assess the public intentions as well as actual impacts of the Trump administration on environmental agencies and their science, researchers at the Environmental Data and Governance Initiative (EDGI) analyzed publicly available reports to Congress over the last several years from seven agencies: the Council on Environmental Quality (in the White House); the Environmental Protection Agency (an independent cabinet-level agency); the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) (both housed within the Department of Health and Human Services); and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), and the National Park Service (NPS)(all housed within the Department of the Interior). We have also taken a deeper dive into one of the most affected of these agencies, the EPA. There, we supplemented the publicly available data with information received from several FOIA requests as well as from interviews with former and current EPA staff.

Within the White House

During his presidential campaign, Trump’s repeated disavowals of being “a believer” in “man-made climate change” famously signaled a disdain for the environmental sciences. Since Trump’s inauguration, his White House has perpetuated and concretized this destructive view. As we noted in Part 1 of this series, the Trump administration’s characteristic approach to environmental policy-making has been to seek out new, legalistic ways of side-lining science that with striking consistency, ease purported burdens on businesses and their profits. In addition to its many policy consequences, Trump’s “disbelief” in accepted science portended the current dearth of voices on behalf not just of environmental but of any sciences at the top levels of the executive branch. This exclusion of science from Trump’s White House has carried straight through from inauguration to the current day. Impacts of this attitude’s impact across White House offices are outlined below:

Departures and Doubt on the National Security Council. As is now well known, the White House’s National Security Council’s by late 2018 had lost its prominently positioned pandemic response team, set up in the aftermath of the 2014-15 Ebola epidemic. This highest-level body for advising the President on security matters, more generally “crippled” by unusually high levels of turn-over, had by 2019 lost a homeland security adviser charged with global pandemic response, a senior director for global health security and biodefense, and a director for medical and biodefense preparedness, none of whom were replaced. In late 2018, the NSC did bring onboard a qualified physicist, William Happer. However, this 79-year-old emeritus Princeton professor appears to have gotten the nod largely because of his outspokenness on a topic outside his own expertise (optics and spectrometry), as a critic of climate science. Despite this top-level access to the president and his advisors, Happer was unsuccessful in pushing through his pet idea of a red team/blue team evaluation of federal climate science. He left after a year, concluding his idea had fallen victim not to any change of heart but to a growing nervousness among the President’s advisors about the “political implications” of such an exercise. Still finding the President “very sympathetic,” Happer insisted the administration had just decided to “lay low on climate change.”

From Climate Action to Extraterrestrial Threats at the Office of Science and Technology Policy. During the Obama Administration, a card-carrying environmental scientist, John Holdren, had led the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, enabling him to become “among the chief architects of the Obama administration’s Climate Action Plan.” In pointed contrast, for its first two years the Trump administration left this leadership post vacant and let the office’s staff dwindle down to 50, compared to 130 during the Obama years. In early 2019, the Trump White House finally filled this inner-circle role, also by turning to an environmental specialist. Tapping atmospheric scientist Kelvin Droegemeier to lead the OSTP, the White House surprised and pleased leaders of the nation’s leading scientific organizations, accustomed to two years of White House obliviousness to their pleas. Having established his reputation as an investigator of “extreme weather,” however, from his Congressional hearing onward Droegemeier remained evasive about how seriously he took the overwhelming scientific consensus around climate change. He then pursued an agenda significantly constricted in comparison to his predecessor, largely bypassing not just climate change but many other burning environmental questions. Instead, as across so much of the executive branch under Trump, he has sought mainly to serve and protect the private sector.

Above all, Droegemeier’s OTSP has prioritized “unleashing American discovery and innovation,” not so much through public investments as by getting the government out of business’s way. In line with so many other policy initiatives of the Trump White House, OTSP sees its job here as mainly “eliminat[ing] unnecessary administrative burdens” to “streamline ways to bring those discoveries from the lab into the marketplace.” Carefully tip-toeing around any environmental problems for which the private sector might be held even somewhat responsible, the Trump-appointed OTSP has chosen to focus much of its environmental work around extra-terrestrial dangers, of “near-earth object impacts” such as asteroids and space weather events, like solar storms and flares.

From Protection to Profitability at the Council on Environmental Quality. The Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ)’s historical role has, from the 1970s through the 1990s, been data gatherer and reporter on federal environmental activities as well as a leader of cross-agency activities to improve environmental protections. Trump’s CEQ has definitively abandoned most of those roles. While the CEQ’s decline had begun at least as early as the Clinton Administration, when it ceased annual reporting on the nation’s environmental quality, the skid has accelerated under Trump, further depriving the White House of any professionally or scientifically informed voices for environmental science. Down to 19 staff Full-Time Equivalents (FTEs) by 2016, the CEQ remained without an appointed leader throughout its first two years under Trump. Finally, in January 2019, after staff had dwindled another third to only 13 FTEs, the lawyer and former Republican Congressional aide Mary Neumayr was appointed to direct the Council (EDGI compiled data).

Neumayr, who’d served for two years prior as CEQ’s chief of staff, steered the CEQ to once more collaborate with other environmental agencies, but mainly around what she framed as the council’s “core responsibility.” That, as she expressed her view at the Congressional hearing leading to her appointment, meant “overseeing the implementation of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) by Federal agencies.” Her pared down CEQ set about spearheading a revision of NEPA guidelines that would speed and “streamline” its decision-making process for federally funded infrastructure and other projects. As part of this “streamlining”, the new guidance excludes consideration of longer-term or cumulative environmental dynamics, which require scientific study to illuminate. Among the chains of causations to be excluded were effects of or impacts on climate change associated with a project, which a NEPA guidance written in the Obama administration had sought to incorporate. In announcing their own NEPA revision, both Neumayr and President Trump himself framed all that scientific scrutiny they seek to jettison as holding back business profits (as Trump put “the builders are not happy [with NEPA]. No one is happy.”) and slashing jobs. In Neumayr’s words, NEPA-imposed “delays deter investments, and…make our country less economically competitive.”

The other main CEQ initiative under Neumayr sounds more science-friendly: an “Ocean Policy Committee” shared with OSTP. Upon closer examination, however, the science for which it calls is to be carefully steered into the Trump administration’s favorite channel: to enable private sector money-making. Aiming to map and develop permit systems and “partnerships” for exploring and exploiting oceans, the Ocean Policy Committee has a goal laid out by Presidential declaration: “to improve our Nation’s understanding of the vast resources in our oceans.” An op-ed by Neumayr and Droegemeier in Fox Business affirms the administration’s prevailing view of oceans as “resources,” clearly prioritizing the usefulness of research for private, market-oriented development over ways it may serve to enhance ecological protections. As with so many other of the reconfigured missions of environmental agencies under Trump, espousal of ocean science must first pledge allegiance to private economic ends—how oceans furnish “new sources of critical minerals, biopharmaceuticals, and energy.” Only subsequently in more subdued tones do Trump and his appointees go on to acknowledge ecological or health protection as goals: how ocean research may also reveal “areas of significant ecological and conservation value.”

Slashing Science-Based Agencies: Comparative Targeting and Tolls

Within the federal agencies, declines in scientific capacity have been prodded by persistent if often stymied efforts of political leadership to defund, reshuffle, and otherwise frustrate thousands of scientists and other experts who have made careers there. Chief among the provocations are the annual budget proposals emanating from the White House’s Office of Management and Budget. Its constrictive visions for federally conducted or funded scientific work offer a yearly reminder of how little the current political leadership values environmental science itself and the many career staff who pursue it.

Although internal documents are not yet available to definitely show just how and why OMB’s cuts for different agencies were actually decided, EDGI’s interviews with career employees at the EPA and other agencies shed some light on the process. They suggest that OMB is allowing input only from the highest-level political appointees inside the agencies—if that—prior to submitting its budget proposals to Congress. Trump’s proposed budget faltered even starting with a Republican Congress in 2017, through a relatively bipartisan defense of environmental science-dependent executive agencies. Although the Trump Administration mostly loses these Congressional battles, the agencies most targeted by its budget proposals are nevertheless suffering the greatest actual funding cuts.

Environmental Sciences in the Bull’s Eye. Side-by-side comparison of White House-proposed cuts across different kinds of science-based agencies reveals a special animus against environmental and public health. Four years of Trump budgets show this administration to be no friend to science, but especially not to science that might inform environmental policymaking. The National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH)—ever since the post-WWII years, the greatest federal bulwarks of American science—have been repeatedly slated for significant cuts under Trump (see chart 1). But the cuts for these agencies have been consistently less than those for agencies sponsoring environmental or public health science that can have policy-making implications (Chart 1).

Average proposed cuts for most of these latter, including the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, the National Park Service (NPS), the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), ranged between 14% and 19%. Of all eight agencies, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has faced the greatest budgetary challenge from the White House, by far. White House-proposed EPA budget cuts have averaged nearly twice as high as those for these other environmental agencies.

Though none of these agencies suffered cuts as deep as those proposed by the Trump White House, neither did they escape unscathed. As shown in Chart 2, Congress’s defense of these agencies has proven decidedly uneven. Only the NSF, an agency with relatively few of its own scientific staff or research, and the NIEHS, have gained in funding without losing staff allocations. For the NIEHS, however, the stable staff ceilings reported to Congress don’t capture actual personnel loss. Interviews suggest losses may have reached ten percent in Trump’s first year, when hiring was frozen, before recovering somewhat through new hires. The NIH has gained a significant increase in its budget over the last three years thanks to Congressional support. But like the NIEHS, it ordinarily undergoes much turnover in staff as scientists rotate between its intramural programs and academic labs. For it as well, a hiring freeze over the first year of the Trump administration was especially crippling, and it has yet to recover. Of the other five environmental-science dependent agencies (NPS, CDC, NOAA, EPA, and FWS), only the National Park Service garnered enough Congressional support to boost its appropriation substantially, much of the extra for backlogged maintenance and construction, though still suffering a reduction of personnel. Most crippled have been those agencies that lost both staff and budget or saw only small budget gains (after inflation): the CDC, NOAA, FWS, and the EPA.

What seems clear is that especially for science-dependent environmental agencies, countervailing support from Congress has failed to prevent significant declines in budgets for some, and in staff for nearly all. While the Fish and Wildlife Service was already relatively small (with a budget just over $1.5 billion and staff FTEs of 8,552 in 2016), the three largest of these four, the CDC ($12.8 billion and 11,421 FTEs), NOAA ($5.8 billion and 12,259 FTEs), and the EPA ($8.2 billion and 14,777 FTEs in 2016), have endured the biggest hits. Though more slowly than envisioned in its budget proposals, the Trump administration has been shrinking science-dependent agencies to conform to its own minimizing vision for them—especially through reductions in staff.

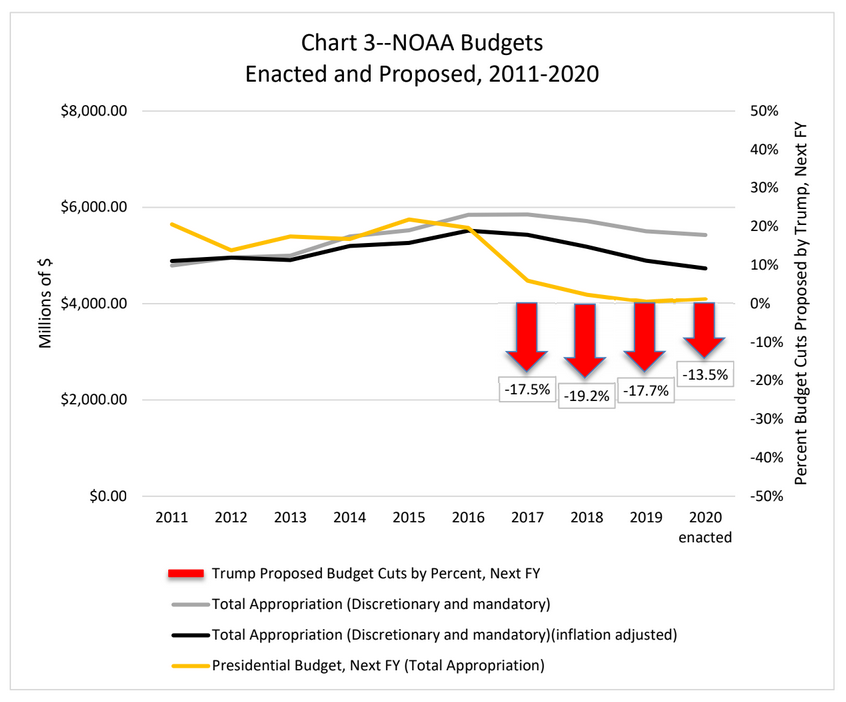

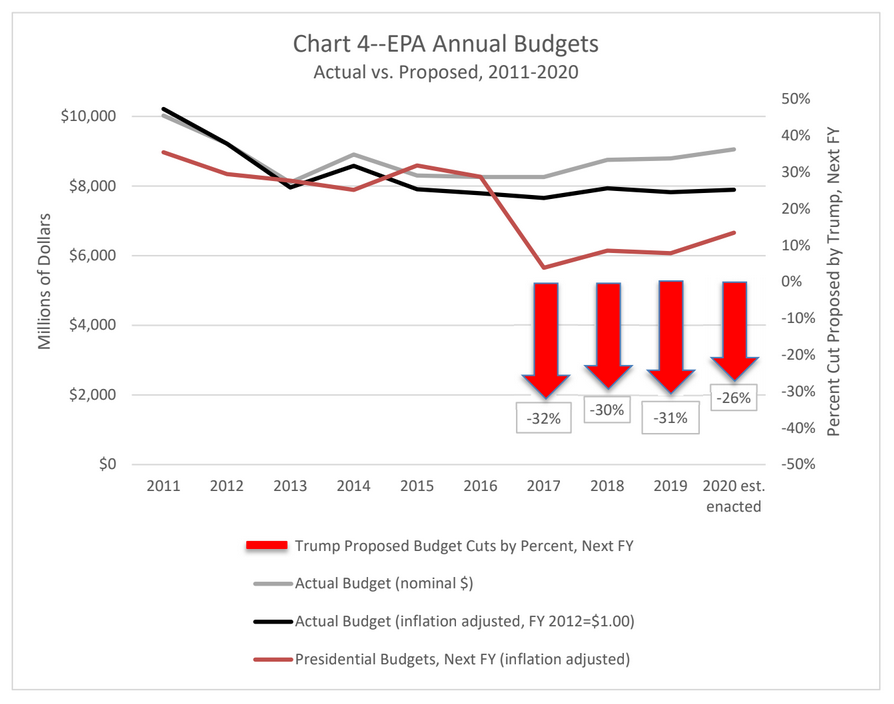

Comparing NOAA and EPA. To better understand the variations in decline between agencies, it helps to consider their differences in functions and long-term funding trajectories. Most (over 90%) of NOAA’s relatively steep budget decline over the Trump years came within its National Environmental Satellite, Data and Information Service, largely through the downsizing of satellite and related technology programs—programs that had ramped up the agency’s budget during the Obama years, under the approval of a Republican Congress (chart 4). That same Congress consistently chopped away at Obama’s budget proposals for EPA, leading to years of shrinking budgets and staff at that agency that prepared the ground for Congress to go along with the Trump White House’s still more draconian proposals (chart 3).

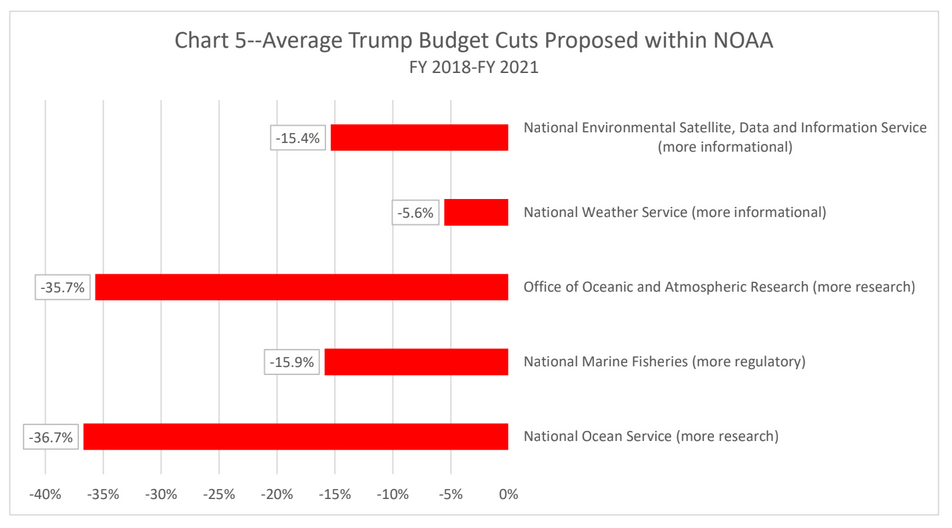

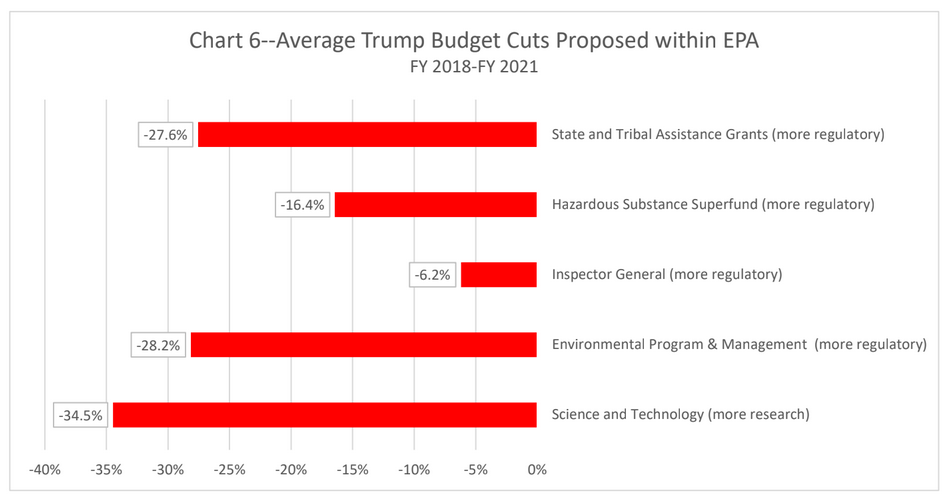

The White House has indeed singled out the EPA for the most ambitious swings of its budget axe, and a more detailed look at which parts of each agency are targeted shows the consistency of its strategy for selecting the deepest cuts: science with potential relevance to environmental policy is in greatest jeopardy. EPA is, more than anything else, a regulatory agency, so over 60% of the EPA’s workforce was devoted to “environmental program and management”—a slice of this agency severely and consistently targeted by White House budget proposals (chart 5). NOAA also conducts some regulation, for instance setting and enforcing rules for fisheries, which has also earned proposed budget cuts comparable to proposed cuts to EPA’s program-and-management work (24% in Trump’s FY 2021 budget for instance). But NOAA’sregulatory activities comprise a tiny share of its mandate compared to EPA. Nor does it have programs comparable to the state and tribal assistance grants, through which EPA supports regulatory and enforcement work at lower levels of government. Instead, across NOAA’s National Weather Service, satellites, fisheries management, and Marine and Aviation Operations, a much greater share of NOAA provides public services that are more technological and informational. The Trump White House has still proposed to cut the budgets of these essential activities. But proposed cuts there don’t come close to those for NOAA’s office conducting environmental research pertaining to climate change (Chart 6).

Charts 5 and 6 demonstrate the strikingly commonality in the White House intra-agency cuts for these two agencies: the most science-centered wings of both are targeted for the biggest reductions. EPA’s “science and technology” budget line includes much of the funding for its Office of Research and Development. NOAA’s National Ocean Service includes programs in “coastal science” as well as “ocean and coastal zone management”; its Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research houses an entire climate program as well as other research programs devoted to “air chemistry and weather” and oceans, coastal areas, and the Great Lakes. Ranging between 34.5% to 36.7%, the cuts proposed for scientific research on the environment at both the EPA and NOAA are remarkably consistent in their severity.

Trump budget justifications for both agencies also share something else: an eagerness to distinguish “core” missions from those presumed less central or somehow not really mandated. For instance, in its budget justifications, NOAA’s leadership—Trump appointees—argue for confining the agency to the “core space-based observational capability” of its existing satellites going forward. Among the stated reasons is that it has already developed and been launching improved weather satellites, and because “more nations [are] launching operational satellites …and a commercial market…may be able to provide certain observations more efficiently” (p. NESDIS-2).

The budget justifications to Congress for EPA’s proposed cuts are even more insistent about singling out that agency’s “core” missions, in ways that sideline public pursuit of or support for environmental science. From “core requirements to meet CAA [Clean Air Act] obligations” (p. 181) to “core water programs” (p. 224), the word “core” is mentioned 119 times in the EPA’s FY 2021 budget justification to Congress, often in conjunction with a proposed cut or abandonment of an existing program. Especially for a regulatory agency like the EPA, a quest for “core” regulatory functions closely dovetails with the systematic disinvestment also being sought in the agency’s scientific capacities.

In this case, it has meant turning back the clock on EPA’s long-standing, evolving use of science to implement established mandates of environmental law. But when only those regulatory programs guided and validated by science of the 1970s or 80s are valorized as “core,” then not just more recent environmental concerns and programs but the newer scientific fields and methods that have guided them become expendable. In calling for the elimination, for instance, of the EPA’s program on “Global Change Research”, EPA’s political leadership framed such moves as a return to activities presumably authorized under its original laws: to “decision-making related to core environmental statutory requirements” (p. 817). In this case, abandonment of research into climate change is justified by downgrading the agency’s obligation to to regulate greenhouse gases under the Clean Air Act, despite a Supreme Court decision and its own endangerment finding. More generally, such moves are reenvisioning the EPA itself and the statutes it enforces. Less willing or open to applying our nation’s environmental law in ways that are informed or guided by science, the Trump Administration is suffocating their dynamism, making them less adaptive to technological and environmental change across our nation and world.

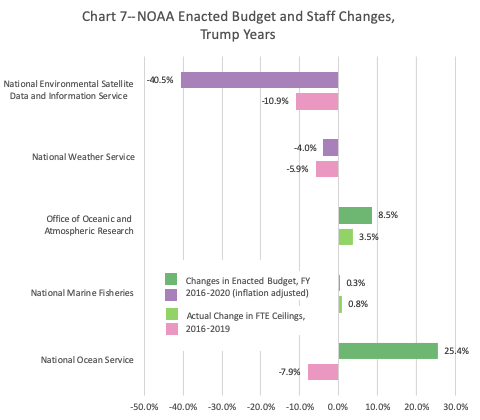

Three and a half years into the Trump administration, many of the science-related activities at NOAA have fared better in final Congressional deliberations and actual budgets than those at the EPA. NOAA’s technology-heavy satellite and data collection program has indeed seen big budget declines, as the administration has sold enough Congress-people on sustaining only the agency’s “core” work there, persuading them that other nations’ or private satellites can and will fill in. But Congress has especially favored the two wings of NOAA that its climate and much other research, through substantial increases in their budgets. (Chart 8).

At the EPA, on the other hand, the Trump years have had a more destructive impact across the board (Chart 7). Only the state and tribal grant program has seen significant budget growth. All other major lines of work have declined both in budgets and personnel. Among all these agencies, the EPA—far and away the most targeted by Trump budgets—has also suffered the greatest actual hits. And its work in science and technology has sustained among the biggest blows.

The budget shortfalls have been especially severe for agency programs and offices undertaking scientific research (Chart 9). Funding lines designated as “research” in EPA’s budget have plummeted over 23%—a greater percentage than that of its science and technology work as a whole. “Air and Energy”, formerly “Air, Climate and Energy” suffered a 22.5% loss despite having stricken “climate” from its name. But the cuts extend much further. Studies of community-level and water resource sustainability have also seen funding curbs. The greatest reduction in research funding has come in chemical safety and sustainability. It has lost over a third of its funding, despite rising concerns about untested chemicals that only four short years ago, spurred a bitterly divided Congress to act.

Overcoming its sharply partisan divisions, Congress in 2016 became so worried about chemical safety and sustainability that it passed the Frank R. Lautenberg Chemical Safety for the 21st Century Act. The Act, arguably the most ambitious environmental legislation to make it through Congress in recent times, handed the EPA a new and more powerful mandate to address the ongoing problem of chemical safety in the US. Despite the long-standing existence of a Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA, passed in 1976), thousands of chemicals used in commerce have not been adequately evaluated for carcinogenicity or developmental and reproductive toxicity, among other health and environmental impacts. The Lautenberg Act was designed to overcome TSCA’s shortcomings in this respect, yet it provided no extra fund to accomplish its mandate. That EPA’s political leadership has been quietly slashing funds for investigations into the health impacts of these chemicals–whether or not Congress itself is fully aware–raises additional questions about just how it is implementing the new law. The agency’s abandonment of its own research in this area adds to the concerns that have been raised about how its “new TSCA” implementation is also bypassing existing science about toxics (for instance, on asbestos, and more generally by legalistic restricting the effects and exposures to be considered in evaluating toxics).

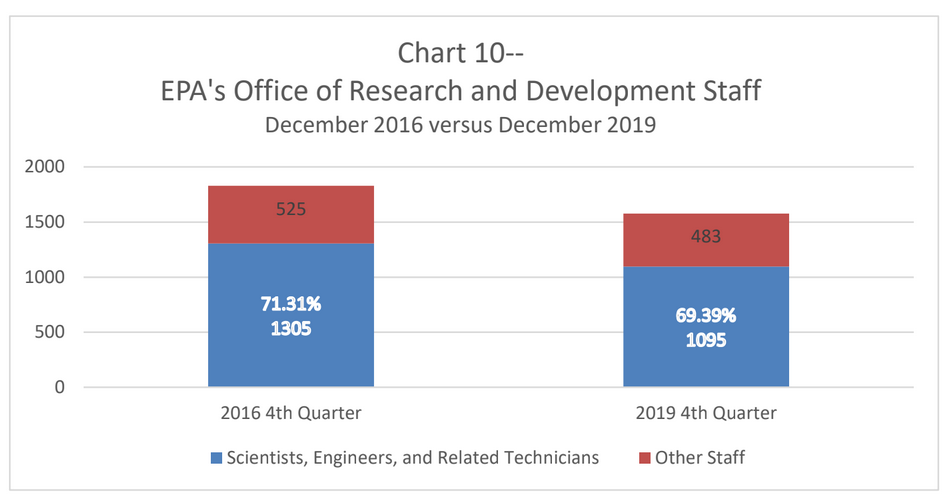

As funding for EPA’s own and agency-supported scientific investigation has declined, so has the Office of Research and Development (ORD)’s staff. The ORD is EPA’s main wing for scientific research as well as technological innovations. ORD staff oversee the agency’s labs, conduct research, and distribute extramural grants, based at agency headquarters and nine other centers around the country. ORD staff reduction has outpaced the overall decline in science-and-technology FTEs across the agency as a whole. While overall ORD staff onboards have declined 13%, those in ORD classified as scientists, engineers, and related technicians have dropped by 16%, slightly more, bringing their share of ORD’s staff down to 69%. Extramural grant programs have generally shrunk, and some, like one shared with NIEHS to fund research centers in children’s health, have been entirely abandoned. As “a natural outcome of the decades-long decline in [ORD]’s funding and personnel levels,” the agency has also been reorganizing. Pitched by leadership as a “rightsizing” of EPA’s research wing, this ongoing reorganization foists an Office of Science Advisor (formerly with direct access to the Administrator) into ORD and folds other offices and research centers together, thereby shutting some sites including the Nevada-based National Center for Exposure Research. While framed as a response to earlier downsizing, this effort may well wind up justifying a further shedding of ORD staff and research programs.

The Decline in EPA Staff: A Brief Anatomy

“We are going to get rid of it [EPA] in almost every form. We’re going to have little tidbits left. But we’re going to take a tremendous amount out.” Donald Trump, March 2 2016 https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/19/us/politics/epa-faces-bigger-tasks-smaller-budgets-and-louder-critics.html

Why has the EPA been so singled out by the Trump administration? Their obsession with “getting rid of” the EPA has deep and extensive roots in conservative circles. These roots can be traced in the rise of an explicitly anti-environmental conservatism since the 1980s, in the vast new infusions of corporate money supporting this political movement, and in closely allied, long-building campaigns to cast doubt on climate science to forestall regulation of emissions from burning fossil fuels. Certainly EPA has stirred corporate and right-wing animosity through its role as the nation’s main regulator of greenhouse gases, as authorized in 2008 under the Clean Air Act by the Supreme Court. More broadly, of all the agencies examined here, the EPA provides the most fodder for the twin animosities driving this anti-regulatory agenda: against the encroachment of environmental laws and policies on business activities, and also against the environmental sciences, whose new or confirmatory knowledge can wind up bolstering new rounds of policy- or law-making. Over the last three decades, arguably no federal agency has more successfully yoked the pursuit of environmental science to the implementation and enforcement of our nation’s environmental laws.

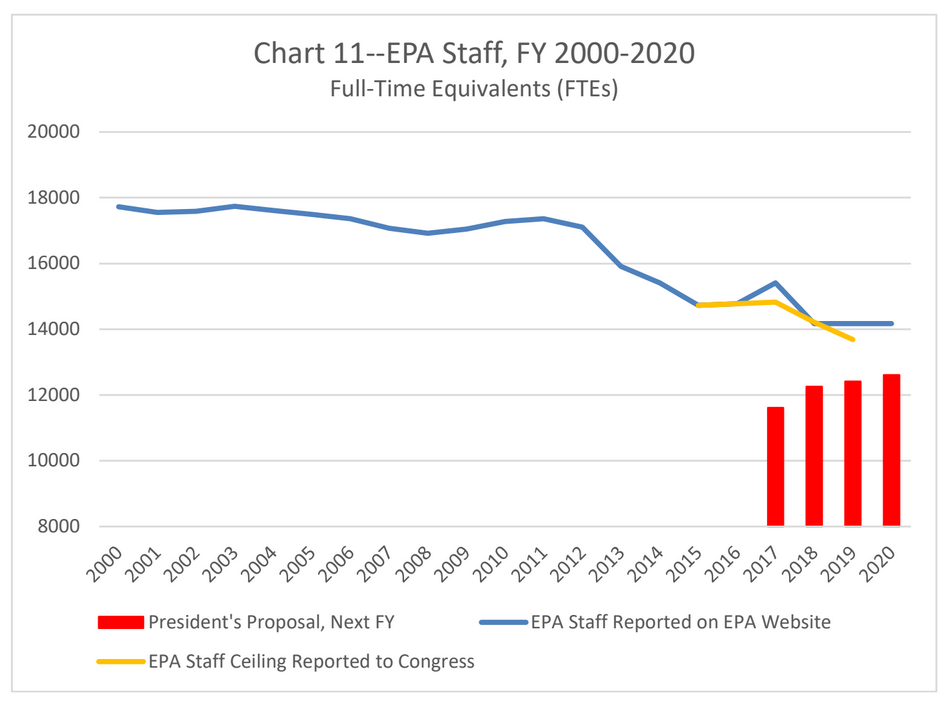

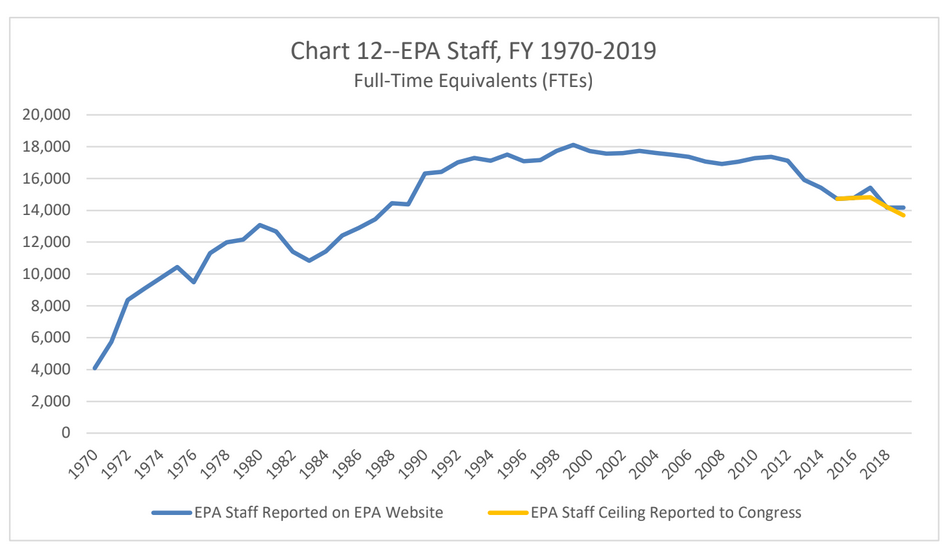

Radically shrinking the size of EPA staff was one of the original goals of the Trump administration. Each year, the administration’s proposed budgets have included large proposed reductions not just of the agency’s budget but of more than 20% of its staff (chart 11). By imagining they can reduce the EPA to minimal functions they deem “core” and rewriting rules to try and make scientists and their research less necessary to the work of environmental regulation, they studiously ignore the agency’s long-standing dependence on science, an integral guide to its work ever since the EPA first set out to implement its earliest, exceedingly broad and vague congressional mandates. Although the Trump White House has lost four bids to persuade Congress to shrink agency resources far more drastically, it has made significant progress whittling down the staff that enable the EPA to do its job.

By 2019, EPA’s published data on staffing levels show a 21.7% decrease from 1999 when staffing reached its historic height (18,110 that year, as opposed to 14,172 FTEs in 2019 as reported on its website; see Chart 11). Whereas in 1999 there was approximately 1 EPA employee for every 15,074 US residents, by 2019, that ratio has widened to 1 EPA employee for every 23,161 US residents. Even after staffing levels underwent their first big slide early in the Reagan Administration, by 1983 EPA’s per capita staffing level was still more favorable (1 employee for every 21,583 residents) than it is today.

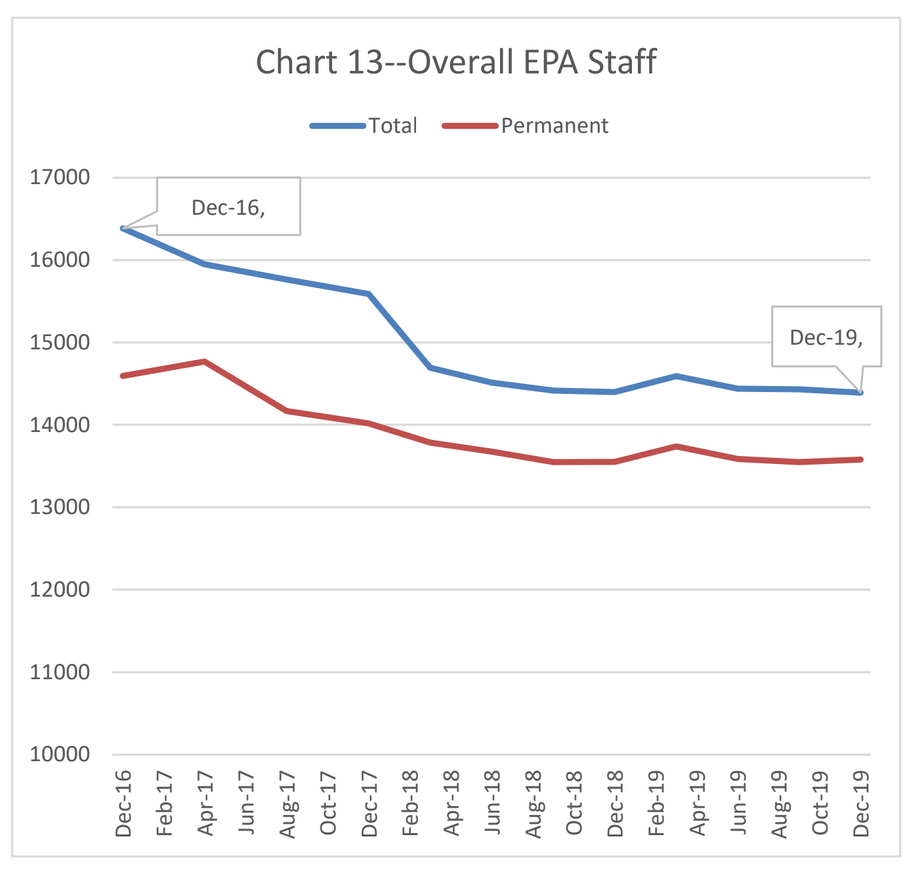

While the yearly staffing levels EPA lists on its website indicate a decline of 7.4% since 2016, staffing data EDGI obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request suggest a bigger dip. In December 2019 there were 14,392 total EPA staff listed as “onboards,” down from 16,385 in December 2016, a loss of 1,993 positions that represents a decline of 12.2% in total agency staff. By the end of last year, staff levels had fallen to where they were during the late 1980s, despite substantial growth to the agency’s work load over the same period.

The pattern of decline suggests important dynamics behind it: a shedding of temporary employees as well as the heavy hand of Scott Pruitt, before he resigned in July 2018 and was replaced by Andrew Wheeler. EPA’s ranks of temporary employees shrank nearly 55%, considerably faster than the 7% drop in its permanent staff (Chart 13). This indicates that fewer interns, trainees, consultants, and advisors were rotating through the agency’s offices. So far as we can also tell from our interviews, very few staff departures came through the dreaded “reduction in force,” or firings. Instead, most are due to decisions made by career staff themselves, albeit in the context of policies and pressures emanating from the agency’s political leadership.

To accomplish at least some of what their budget proposals could not, Trump political appointees have encouraged a steady stream of departures from the agency’s staff, many of whom have been onboard for decades. In the 2018 EPA workforce, 42% of employees were reportedly eligible to retire by 2023. The biggest early staff declines came from a one-time buy-out offer extended to EPA employees 50 years old and more, in summer 2017. That initiative came in the midst of a Scott Pruitt-led effort to transform EPA’s mission that hiked the hostility many career employees felt from agency leadership toward their work. EDGI’s “EPA Under Siege” (June 2017) as well as subsequent media coverage captured how these dynamics played out in EPA’s hallways: from closed doors to internal poster campaigns, to the resolutely deaf ears of political appointees to input from career staff. Though overt denigration of career staff and scientific advisors has diminished under Wheeler, the main decision-making circles remain closed to all but the political leadership, yielding decisions that clash deeply with many staff members’ sense of the agency’s mission. Continuing frustration of EPA’s staff has contributed to the retirements and attrition, though more recently, our interviewees suggest, many now plan to hang on at least until the November election, hoping it will bring a change in leadership. Nevertheless, Trump political appointees have leveraged administrative powers of transferring and hiring to alter the agency’s size and orientation. Starting with a hiring freeze that ran for over a year, they have shrunk down staff numbers gradually overall, but at a quicker pace in their least favored, presumably more “peripheral” parts of agency.

Staff Losses by Office. Staff departures have impacted nearly every corner of the agency, though not evenly across regions (Chart 14). Staff losses in EPA regional offices have varied from approximately 8% in Region 8 (CO, MT, ND, SD, UT, WY and 28 tribal nations) to 14.6% in Region 3 (Mid-Atlantic, including DE, DC, MD, VA, WV, and 7 federally recognized tribes). Headquarters and EPA laboratories, which provide the analytical capacity for various programs such as Water, Superfund, Air, and TSCA, have lost 13.1% of their total staff—more than most of the regions, which averaged 11% drops. The result conforms with the leadership’s early rhetorical embrace of “cooperative federalism”–“empower[ing] the states to take on more regulatory responsibility, while preventing the overreach of federal agencies.” Even as the administration has subsequently reverted to battling California and other states that reject its environmental rollbacks, it has accomplished a slight decentralizing of EPA’s overall workforce beyond Washington, D.C., shifting its balance toward the regions.

The agency’s headquarters offices have all faced staff reductions, though some much more than others (Chart 15). Losing the biggest shares of their existing staff are those parts of the agency charged with inspection and oversight. Since December of 2016, the Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance has lost an astonishing 22.7% of total onboard personnel. The Office of the Inspector General, charged with overseeing the agency and conducting independent investigations into agency performance, has lost 18.5% of its workforce. The Administrator’s Office, though reportedly expanding its ranks early on under Pruitt, has since become among the most pared back of offices, weathering a 20% staff cut since 2016 (in part through departures of personnel devoted to children’s health and climate adaptation). Of all the media-program offices, the Office of Land and Emergency Management, which administers Superfund and hazardous waste laws, has fared the worst, enduring a 14.5% cut. But even those offices administering the EPA’s earliest and arguably most “core” of programs, the Offices of Air, of Chemical Safety (pesticides and other toxics) and of Water, have lost significant shares of their staff, with reductions ranging from 9.4% to 3.6%.

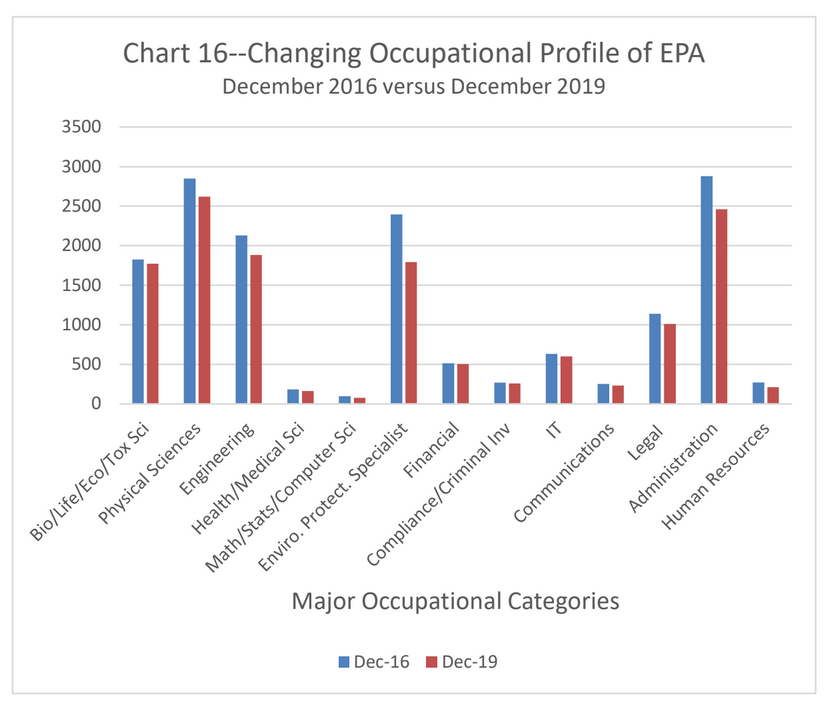

Staff Losses by Occupation—Over the three years of the Trump administration, every major occupational category at the EPA has also seen losses. Its ranks of scientists have thinned, so too of those who are scientifically trained but whose work revolves mostly around policy or enforcement decisions. The agency has also lost many other employees; approximately 15% of its administrative staff, for instance. The cumulative loss of scientists, engineers, and related technical staff has roughly kept pace with losses of these other kinds of staff, keeping each category’s share of the agency’s workforce more or less constant. But while fewer administrative staff may have impaired the agency’s general efficiency, losses of the scientifically trained hobble the agency’s work in other critical ways. The EPA is losing its ability to know the environments it seeks to regulate, to recognize the pollution and other infractions it is supposed to control. Writing regulations, imposing penalties, and seeking other remedies for environment problems all demand reliable knowledge about exactly what those problems are, how bad they are, and whether or not the agency’s responses to them are working (Charts 16 and 17).

The biggest staff loss in any category (not just among scientists) is that of “Environmental Protection Specialists.” Nearly 2,400 strong at the end of the Obama administration, this 14.6% of the EPA’s workforce had qualifications that included “a bachelor’s degree in environmental science or a science-related field.” Essentially applied environmental scientists, they wield this knowledge in agency programs to control pollution, assess and remedy environmental damage, and generally “to protect and improve environmental quality.” EPA has more of these specialists than any other federal agency, but their ranks have plummeted under Trump, to 12.4% of a shrinking agency. While widely distributed throughout the agency’s various “media” program offices (i.e., for air, water, etc.), they have become especially scarce in the agency’s biggest loser of overall staff, the Office of Enforcement and Compliance, where their ranks slipped from 69 to 41 (a 40.6% drop) (Chart 18).

The losses of physical scientists, engineers, and life scientists, while in percentages not as dramatic as those of protection specialists, still loom large, as these groups make up substantial proportions of the agency’s overall staff. Over the course of three years up to the end of 2019, the EPA lost the expertise of 247 engineers, 228 physical scientists (geologists, chemists, physicists) and 63 life scientists (ecologists, toxicologists, plant physiologists)—a critical 3.5% of the agency’s workforce that has not been replaced.

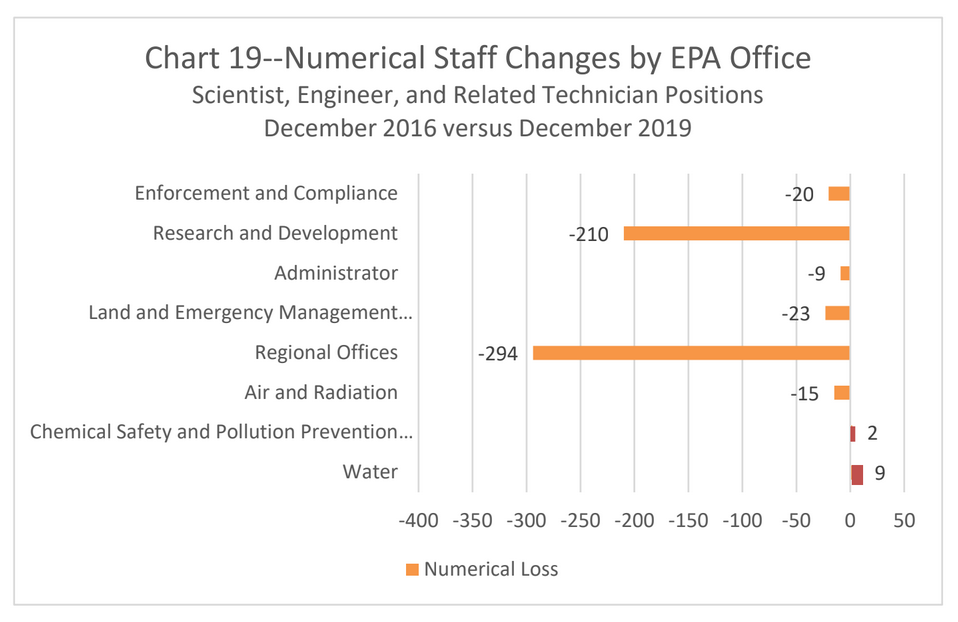

These losses have impacted different parts of the agency differently, offering a revealing window into the overall strategy by which the Trump administration has sought to curtail the agency’s work (Charts 18 and 19). An administrator’s office intent on re-writing environmental rules to exclude scientific findings and influence has, not surprisingly, shed over 15% its own scientific staff. While the enforcement office is generally less dependent on scientific investigations than other parts of the agency, the administration’s efforts to reduce enforcement have made this office the biggest percentage loser of on-staff scientists, engineers and related technicians,, down from 123 to 100. Similarly, the ten regional offices, where the bulk of the agency’s hands-on oversight and enforcement occurs, have lost 294 scientists and engineers, the largest overall number. And with an administration set on devolving research itself into a more peripheral function of the EPA, the central office most heavily staffed by professional scientists and engineers, its Office of Research and Development, has endured a loss of 210, the biggest numerical decline by any one office.

Staff Losses by Seniority (Grade). In addition to the loss of scientific and engineering expertise through staff shrinkage, the EPA has also lost decades of other kinds of knowledge, more experiential and institutional. Employees who have been there the longest and shouldered high levels of responsibility make up a disproportionate share of those departing. The EPA’s salary grades are ranked up to 15 on the “General Service” and “General Manager” pay scales, where 15 is the highest salary level, often (though not always) representing the most experience. With so many long-time, older employees, most of EPA’s salaries rank in the top four brackets (Chart 20). In important part because buy-outs were offered to employees 50 years of age and older, a large number of seasoned staff have retired from GS 12 or 13 positions, as well as GS 14 or 15 staff levels. Looking at how many positions in each salary grade have been lost during the Trump years shows just how top-heavy the depletion of EPA staff has been.

A full third of positions that have not been refilled are at the level of GS or GM 13, the third highest salary bracket in the agency (Chart 21). While GS 13s remain by far the biggest share of EPA staff (Chart 20), those in the two highest brackets comprise another 12% of the losses, and 51% of the nearly two thousand lost positions lay in the top four salary brackets. By not refilling these mid-to-upper level positions, the agency is cutting salary costs, but at the expense of effective functioning. Not just the scientific and engineering expertise of this senior staff but their abundant other knowledge and skills, accumulated over years and in many cases decades, have enabled what effectiveness this agency has achieved in fulfilling its statutory mandates. Yet with the current political leadership so eager simply to shrink the agency’s capabilities and regulatory footprint, no effort has been made within the agency to try to save, much less assess, what has been lost with all these departures.

Impacts from staff loss. Staffing cuts have a profound impact on both the quantity and the quality of the work the agency can do. In interviews, EPA employees and recent retirees tell of an agency understaffed prior to the Trump administration that in the last three years has been veritably hammered by staff losses. Many staff members have left prior to traditional retirement age, in the prime of their careers, taking decades of accumulated know-how with them. As one staffer put it, “people that probably would’ve worked another 10 years that were eligible for retirement just took off because it wasn’t worth it for them. So we lose a lot of institutional knowledge….you can’t replace those people.” Even when an office head is able to persuade the leadership to “hire some people,” “they’re all getting brought in at junior levels. They don’t really have anywhere near the expertise of the folks that left.”

In those parts of the agency where knowledge of scientific research is especially critical, interviewees report “losing many experienced scientists who have been here for a good number of years.” Some offices are reportedly down dozens of qualified scientists, and are now seeking replacements. Reports one staffer: “there are a lot of young people…that have studied and come out of school that would be good hires.” But coming in only with academic and laboratory training, these newly minted scientists have yet to learn what years of EPA work had taught those into whose old jobs they are stepping. They’ve less experience working with those in those different disciplines, as well as few or no established relationships in offices beyond their own, both of which EPA scientific as well as policy work demands.

Part of the institutional knowledge being lost in the exodus of experienced staff is a well-honed ability to work collectively with those outside one’s own field. Agency work often happens through what one interviewee terms “communities of practice”: even though “they don’t do all the same stuff…they get together, they talk about common issues.” In one case, when a member with thirty years experience retired, two others left, and another who had brought legal expertise to bear got transferred, a manager was able to secure a single youthful hire to take their place. “So that’s four people” with “70, 80 years worth of experience” who were replaced “with three years of experience.” To make matters worse, the new hire began his work under a “new manager who just came to the agency within the last year.”

Loss of departing staff’s experiences also deprives the agency of working relationships forged over time with those in other offices or agencies. EPA’s protracted negotiations with those in other federal agencies, in states and local governments, have long been central to its accomplishments, from cleaning up federal facilities to teaming up to oversee the most difficult and dangerous private polluters. Departures of senior staff disrupt these established ties, decreasing the efficiency and effectiveness of the agency’s work.

A dwindling workforce also forces difficult decisions onto the remaining staff, still expected to sustain their assigned work. When one office had a third of their staff taken away and lost another FTE to retirement, they were forced to settle upon what their program absolutely required to continue their work. As a consequence, they were unable to do any public outreach or engagement. Instead, they work more quietly, eschewing publicity and concentrating only on the bare necessities of their program. Another spoke of an office reduced from “11 or something, down to 4 people,” whose “ability to provide services is greatly reduced.” Tough decisions then follow: “with net loss of people, you aren’t able to cover the breadth and depth of issues and opportunities…so just the scope of what you can take on is much smaller.”

Occurring against the backdrop of an already underfunded and understaffed agency, the EPA’s additional declines under Trump have further impaired the agency’s ability to grapple with basic issues like safe drinking water, sewage sludge, and the cleanup of toxic waste sites. For environmental problems illuminated in more recent decades, the agency’s diminished scientific and investigatory capacity under Trump has arguably become even more debilitating. Hand in glove with the current political leadership’s campaign to roll back rules for climate change, aerial particulates, and toxic chemicals–just to name a few–its corrosion of the EPA’s scientific resources and capacity has increasingly compromised this agency’s ability to reverse course on any of these fronts, much less to spearhead any renewed federal regulatory effort. To do so, the EPA will require not just a u-turn in leadership but a serious effort to replenish its ranks.

Conclusions

For decades, the starvation of federal agencies has been a long-standing problem, both through inattention to their growing needs and through intentional cutbacks of budgets and staff. A 2019 non-partisan report on federal employment notes that the workforce of the federal Executive Branch “has hardly grown in sixty years—there were 1.8 million civilian employees in 1960 and only 2.1 million in 2017,” despite a near-doubling of America’s population and a quintupling of its real Gross National Product. While some environmental and public health agencies were already around in 1960, the EPA and others covered here emerged or grew dramatically soon thereafter. More recently, however, they too fit the general pattern outlined in this report, and its stark warning is becoming ever more applicable to them. Federal environmental and public health agencies’ staffing, capacity and expertise are becoming ever more inadequate for confronting the many threats and challenges that lie ahead. The Trump Administration has accelerated this corrosion, putting federal environmental governance “at risk of failing” in a significant crisis.

Since coming to office in 2017, Trump’s White House and political appointees have made no secret of their determination to drastically shrink the environmental scientific and regulatory agencies they run. That is the clear message of all four annual budget proposals, which sought to raze federal environmental science and regulation to an extent that is without precedent in modern times. While seeking funding and staff cuts across the gamut of environmental and public health science-dependent agencies – from the CDC to NOAA and FWS – the Trump administration reserved its most aggressive slashes for the EPA.

That choice was revealing: by targeting the EPA, the White House singled out the very agency where science and environmental regulation have been most tightly integrated, to productively and dynamically reinforce one another. This choice suggests that for the Trump Administration, cutting environmental science may be a more secondary goal, means to another it sees as more primary: limiting the scope and sway of our environmental laws, which the Administration sees as suffocating businesses and job creation.

In spite of steady Congressional opposition, the Trump Administration has made significant headway in downsizing our main federal environmental agencies. Over three years, political appointees’ control of relevant agencies, especially on matters of assignments and staffing, has accomplished a significant measure of what Trump budget proposals envisioned. The environmental and public health agencies surveyed here have mostly undergone declines or remained level in staffing; despite Congressional interventions, budgets of these agencies have done little better.

The EPA has indeed borne among the biggest blows. It has lost the largest shares of staff, and its scientific work has also been most effectively and thoroughly curbed. With those departures, it has lost not just people but environmental as well as institutional knowledge. Losing seasoned employees, often in the prime of their careers, has deprived the agency of know-how and relationships that make its work more efficient and effective. Losing scientific expertise cuts back on its ability accurately to assess environmental problems, a key step toward remedying or resolving them. Not surprisingly, the losses of environmental science and scientists at the EPA have coincided with large reductions in both enforcement staff and what EDGI and the EPA’s independent Inspector General found to be a historic drop-off in the agency’s enforcement work.

Projecting forward the pattern of the last three years, another four years of a Trump presidency will likely reduce the staff and budgets of federal environmental agencies still further. Congress has already resisted Trump cuts to these agencies; but the Administration has found workarounds to reduce the agencies without Congressional intervention. So even if a future Democratic Congress passes budgets that bolster environmental science and regulation in the Executive Branch, these agencies’ scientists and labs will most likely continue to dwindle, especially those producing environmental knowledge with policy relevance. While federal environmental science is unlikely to vanish altogether during four more years of Republican rule, its pursuit promises to become ever more siloed off from federal environmental policy-making.

What does it mean for the US, whose federal science was once admired around the world, to jettison a guiding role for science in governmental decision-making, on questions which affect so many Americans’ environments and lives? Over the last three months, we have all witnessed just how profound the consequences of turning away from scientifically informed decision-making can be. CDC laboratory and testing failures prevented the early identification of COVID-19 infections in American communities and allowed the disease to silently spread widely throughout the country. The dramatic loss of life and economic pain the country is now experiencing are in many ways a consequence of the erosion of federal science under Trump, as well as his administration’s devaluing of scientific evidence and leadership.

Similarly, denying and defunding climate science hurtles us toward an uncertain and dangerous future where natural disasters and heat waves will occur with increasing frequency. An already overburdened American public will face mounting health, environmental and economic instability. Heedless of this future, our current political leadership has taken us down a path where our power to challenge ongoing pollution, unconstrained resource extraction, and climate instability is being severely eroded. Since science is one of the most robust tools for holding powerful interests accountable to the public, with federal science carrying special weight, defunding and destaffing federal science effectively erodes our democracy itself.

Should a new administration arrive in Washington that is more environmentally friendly, it will face enormous challenges. Even before it can reverse the many Trump-era policy rollbacks, it also needs to closely examine the diminished capacities for reliable knowledge and institutional know-how bequeathed by its predecessor, and the consequent damages to the levers of environmental governance. To simply rebuild what was there in 2016, it will need to restore resources and staff, bringing more scientists and science back into the federal government. But to reconstruct our federal environmental agencies in ways that truly enable them to meet America’s current environmental challenges, it will need to do more. It should also seek out and establish more durable ways through which science and regulatory policy can more effectively inform one another.

For press inquiries contact edgi.comms@gmail.com