Image by Boyd Norton

By Kelly Evans, Eric Nost, and Sara Wiley

Summary

Legislation being considered by the Canadian Parliament would direct the federal government to create a nationwide strategy to research and redress the disproportionate harms that Indigneous, racialized, and other socio-economically marginalized communities face from industrial pollution. Bill C-226 proposes the creation of new data infrastructures as part of this, following similar efforts in the US such as the recently passed Environmental Justice Mapping Bill. These approaches revolve around the use of environmental and demographic data to “screen” areas for environmental injustices. We argue that the Canadian federal government should adopt an “environmental data justice” approach to implementing Bill C-226 in order to address the intersecting forms of racism that shape how such data is produced, represented, and utilized in decision-making.

We recommend:

- designing metrics on provincial and federal-level enforcement of environmental protection laws, so that improvements can be encouraged;

- emphasizing the economic factors that environmental justice communities may share in common, such as being home to fossil fuel facilities;

- grading these sectors so that they are incentivized to improve across the board.

Environmental Data Justice

Injustice exists in many forms. In contemporary society, people marginalized on the basis of race, indigeneity, and class are discriminated against where they live, work, and play. This discrimination has personal, structural, and environmental dimensions. Since the beginning of colonization in Canada, the dispossession of Indigenous land and rights have equipped white people with unearned privileges to health, wealth, housing, drinking water quality, and environmental quality. The ability for white people to construct, access, and maintain cleaner environments is an expression of environmental racism, defined by Dr. Ingrid Waldron as the disproportionate exposure of Black, Indigenous, and additional marginalized communities to toxic pollutants and other hazards. For instance, the Aamjiwnaang First Nation in Sarnia, Ontario is situated in the heart of Ontario’s “Chemical Valley” and Lincolnville, an African Nova Scotian community, continues to suffer the ramifications of a landfill that polluted water wells decades ago.

Bill C-226 is a National Strategy Respecting Environmental Racism and Environmental Justice in Canada’s Parliament that acknowledges Indigenous, racialized, and other marginalized communities face disproportionate exposure to environmental hazards. If implemented, this legislation would require the Minister of Environment and Climate Change to develop a national strategy to address the harms caused by environmental racism, in part by creating federal-level datasets that link hazards and health outcomes with socio-economic indicators.

Although Bill C-226 is a progressive attempt to address environmental racism, previous efforts to utilize data for environmental justice have involved unjust data collection methods. For example, government-funded research in academic and economic sectors has historically emphasized ‘helicopter science‘, where scientists enter a community, collect data or samples, and leave – not typically informing the communities of their findings. On the other hand, programs that ask communities to collect their own data can introduce a double burden where communities that bear the brunt of environmental hazards are also saddled with collecting the data to prove harm in their community. The use of computer algorithms and artificial intelligence for data analysis is an additional method implemented by federal institutions, however, these have been noted to have “inbuilt colour blindness” that may limit their utility for environmental justice, and possibly perpetuate injustices.

To ensure environmental injustices are addressed in a just manner, Bill C-226 should adopt an Environment Data Justice (EDJ) framework. Developed by the Indigenous-led Environmental Data Justice lab and members of the Environmental Data and Governance Initiative (EDGI), the notion of EDJ challenges the extractivism present in environmental policy and data infrastructures. Adopting an EDJ framework counters how databases are currently used, acknowledging what and whose information is considered valid, and depicts what data goes ignored. It also builds on existing ideas of environmental and data justice to address inequitable access to digital data.

However, EDJ is not just about critiquing data; it calls for applying data in a critical, reflexive, and justice-oriented manner. Rather than using data to prove the existence of environmental racism by running nationwide statistics that correlates hazard and socioeconomic characteristics – an effort commonly used in settler states, one that often ends up perpetuating harm by raising fruitless debates about causation, deferring recognition and disenfranchising communities – we call for using existing albeit limited data to highlight not if environmental racism exists in Canada but which communities are disproportionately burdened with polluting hazards. Below, we show one productive way how, if Bill C-226 aims to create federal-level datasets around environmental racism, it could be done in the spirit of an EDJ framework.

Mapping Environmental Injustices

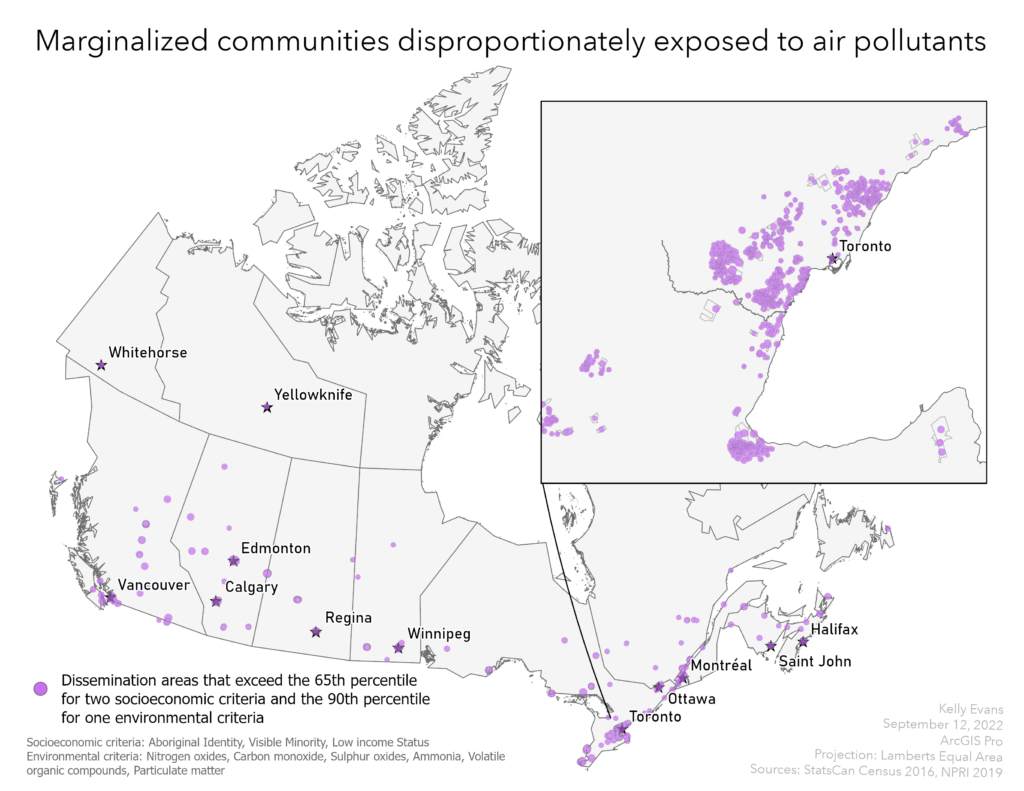

A geographical information system (GIS) is a tool that connects data to a map, visually displaying data to a targeted audience. In the context of environmental racism, a GIS can collate data from provincial and federal databases to visualize where socio-economically marginalized communities are situated in relation to environmental hazards, such as air pollution. The figure illustrated below utilizes data from Canada’s 2016 Census and air pollutant releases from the 2019 National Pollutant Release Inventory to visualize Census dissemination areas with: 1) a visible minority, aboriginal, and/or low income population percentage greater than two-thirds of all other areas in Canada: 2) exposures to one or more air pollutants greater than 90% of all other areas in the country.

The methodology we used to assign these thresholds follows a similar method used in the Justice40 initiative implemented under the Biden administration in the US. Justice40 intends to allocate 40% of federal climate change spending to “disadvantaged” communities that are relatively overburdened by pollution. The Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool (CEJST) is meant to identify which communities count as “disadvantaged.” The tool has its limitations, including disregarding race as a relevant variable. We at EDGI have voiced our concerns about it to the Council on Environmental Quality and provided recommendations to ensure solutions for environmental justice are targeted at the source (i.e., fossil-fueled facilities). There is currently no indication as to how Bill C-226 will achieve environmental justice in Canada; adopting some of the recommendations indicated by EDGI in its comments on CEJST could be a beneficial first step.

Using maps to show policy-makers which communities in Canada are currently facing the brunt of environmental injustice could help policy-makers prioritize enforcement actions towards polluting facilities in those regions. However, our map only illustrates communities in Canada that experience a disproportionate exposure to air pollution – which is not the only form of environmental hazard. Water contamination preventing access to clean drinking water and a lack of green spaces such as parks are additional injustices that Indigenous, low-income, and racialized communities face.

Environmental racism is not new; it was the foundation for colonialism in Canada and has carried through to present everyday environments. The climate and water crisis is progressing, and many of the communities already experiencing these effects have been socio-economically marginalized. However, given governments’ tendency towards data extractivism, it is crucial to recognize the power dynamic that exists in policy-decisions. A strategy to address environmental justice cannot be obtained using current data collection methods – we strongly encourage the implementation of an EDJ framework in Canada’s attempt to address environmental racism.

This would likely go beyond what we’ve done here to focus on root causes rather than identifying “marginalized” or “disadvantaged” communities. While necessary, identifying the places that have been harmed by industrial polluters overlooks those places that benefit from externalizing environmental risks onto them. These communities – who generally consume the most energy and generate the most waste – benefit from not being mapped. This is a double benefit – they are not made the subject of research or policy change and they continue to avoid pollution’s costs. They are “white washed” in data as normal, healthy environments, appearing to not have any EJ problems, when in fact they are disproportionately responsible for them.

We call for:

- mapping industrial facilities that socio-economically “marginalized” or “disadvantaged” communities have in common – such as refineries – and mapping production supply chains and regions of extraction, refineries, and chemical manufacturers;

- mapping resource consumption from those entities and downstream products, as well as shareholder and parent companies;

- developing metrics on provincial and federal enforcement of and industry compliance with environmental protection laws, in addition to metrics that incentivize economic actors to also improve their EJ records.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge our social positions as white settler Canadians. Our identity will limit views and findings in this topic as we cannot personally relate to environmental racism and other forms of injustice experienced by marginalized people in Canada. This article aims to bring attention to these matters. We encourage future researchers and policy-makers to value the perspective and knowledge of these communities, and listen to the voices of Indigenous, Black, and marginalized people in decision making processes.