By Jesse Divalli, Sara Wylie, Gretchen Gehrke

This blog contextualizes changes described in this report.

Over the last year, the Department of Interior (DOI) has adopted a new priority: through the creation of a new webpage and a series of recent announcements and orders, DOI has indicated a desire to make public lands more open for recreational (primarily hunting and fishing) uses than ever before. Though greater public control and access might be an admirable goal in some contexts, in this case it has the appearance of more of a calculated political call to a small portion of the U.S. population, at the potential cost of conservation gains for protected environments and species. The extensive harm done to public lands during the January 2019 government shutdown underscores the potentially disastrous impacts of giving the public greater access while compromising even the maintenance of those lands.

Recreation as a priority

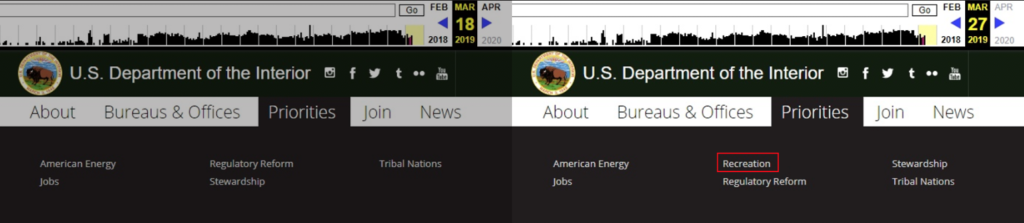

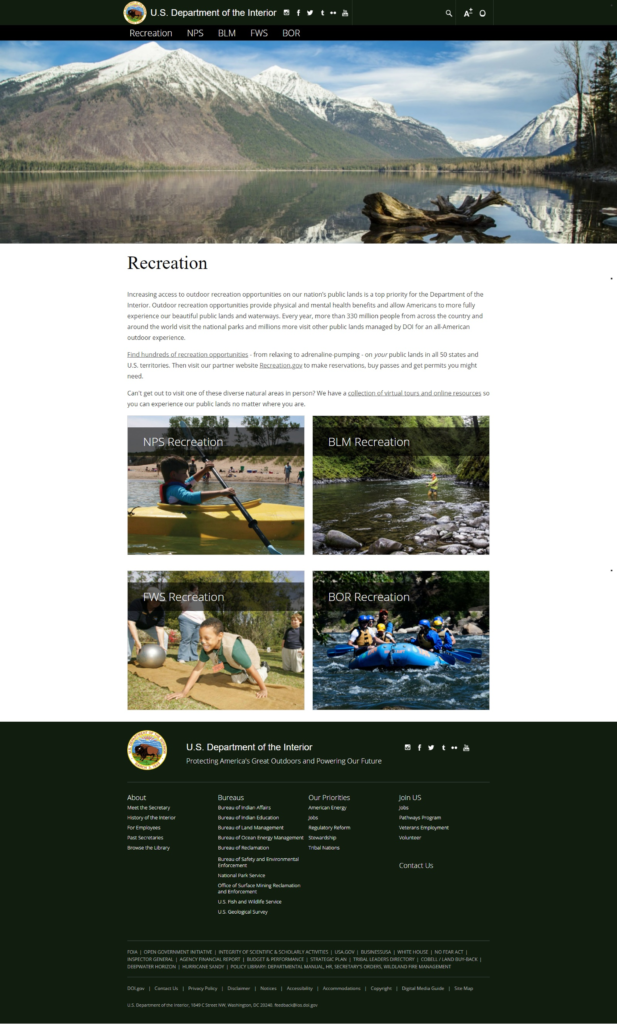

As of March 27, 2019, the DOI added a new link to its dropdown list of “Priorities” at the top of its homepage and across most of its subpages. The new link, “Recreation,” leads to a new webpage of the same title—created sometime before April 4, 2019 when the first snapshot of the page occurs in the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine—which includes text encouraging viewers to discover recreational opportunities on the “millions [of] public lands managed by DOI for an all-American outdoor experience.” Below the text are pictures of people enjoying outdoors experiences with links to recreation-focused webpages for the four primary land managers in the DOI: the National Parks Service (NPS), the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), and the Bureau of Reclamation (BOR). Of these pages, the Wayback Machine does not have snapshots of two (NPS and FWS) prior to April 4, 2019, suggesting that these two pages are new as well.

These changes co-occurred with the announcement in a press release on March 28, 2019 of then-Acting Secretary David Bernhardt’s signing of Secretarial Order 3374, which directs “timely implementation” of Senate Bill 47, the John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act (Dingell Act). The Dingell Act, introduced by Senator Murkowski (R-AK) on January 8, 2019 and signed into law as Public Law 116-9 by President Trump on March 12, 2019, is a broad law implementing several changes to conservation and public land management laws, several new acts encouraging recreational use of public lands, and an assortment of other acts and corrections cleaning up administrative processes and directing the removal of offensive racial terms from various laws.

Sportsmen’s access in Title IV of the Dingell Act

Relevant to the changes observed on the DOI webpage is Title IV of the Dingell Act: “Sportsmen’s access and related matters.” Subtitle B, “Sportsmen’s Access to Federal Land,” includes several sections outlining the new focus on sportsmen’s access and directives to the DOI Secretary in that effort.

Section 4102, “Federal land open to hunting, fishing, and recreational shooting,” supplies the “open unless closed” directive the above-referenced press release references, saying:

Subject to subsection (b), Federal land shall be open to hunting, fishing, and recreational shooting, in accordance with applicable law, unless the Secretary concerned closes an area in accordance with section 4103.

The process of closing federal land to these uses is outlined in Section 4103, “Closure of Federal land to hunting, fishing, and recreational shooting.” This section requires the Secretary to “consult with fish and wildlife agencies” and “provide public notice and opportunity for comment” before any such closure, outlining in a final decision how they arrived at the decision they made. Further, it directs the Secretary to publish an annual list of temporarily and permanently closed locations.

Marksmen will rejoice in Section 4104, “Shooting ranges,” which allows the Secretary to “lease or permit the use of Federal land for a shooting range,” with a few exceptions where such ranges are not to be permitted.

The meat of this Subtitle is in section 4105, “Identifying opportunities for recreation, hunting, and fishing on Federal land.” This section requires the DOI to list and biennially update lands in the jurisdiction of the NPS, FWS, and BLM (the BOR is notably absent) to which the public is not yet provided a means of access and egress by foot, horseback or motorized vehicle, and then to come up with plans to provide such access and egress.

Taken together, the elements of Title IV of the Dingell Act provide a high level of access and consideration to recreational users of public lands—especially for hunting, fishing, and shooting—requiring the managers of those lands to consider such uses in all decisions they make about those lands. It completes the groundwork for embarking on the DOI’s mission to “expand hunting, fishing, and other recreation on DOI lands and waters outlined in the Strategic Plan for Fiscal Years 2018–2022, developed and issued under Ryan Zinke’s watch.

It is no surprise, therefore, that the above-mentioned press release quotes significant praise from sportsmen and recreation groups, which apparently had been lobbying the government for such changes for decades. The one caveat comes in Section 4002, “No priority,” which states:

Nothing in this title or the amendments made by this title provides a preference to hunting, fishing, or recreational shooting over any other use of Federal land or water.

That is, consideration must be made, but no priority given, to recreational uses of public land, leaving wiggle room for the Department to continue to “Shatter” oil and gas lease sales records and “unleash” an energy revolution through continued efforts to “[s]ignificantly cut the time it takes to process Applications for Permit to Drill (APDs) on Federal lands.”

What are DOI’s actual priorities?

What is perhaps most disturbing about these web changes and the amount of energy being put into implementing the Dingell Act is how quickly the changes were made, including creating a priority webpage that is rivaled only by the “American Energy” webpage in terms of depth and links to external content immediately useful to the public. Meanwhile, the pages for the “Tribal Nations” priority and the “Stewardship” priority languish from neglect and lack of specificity.

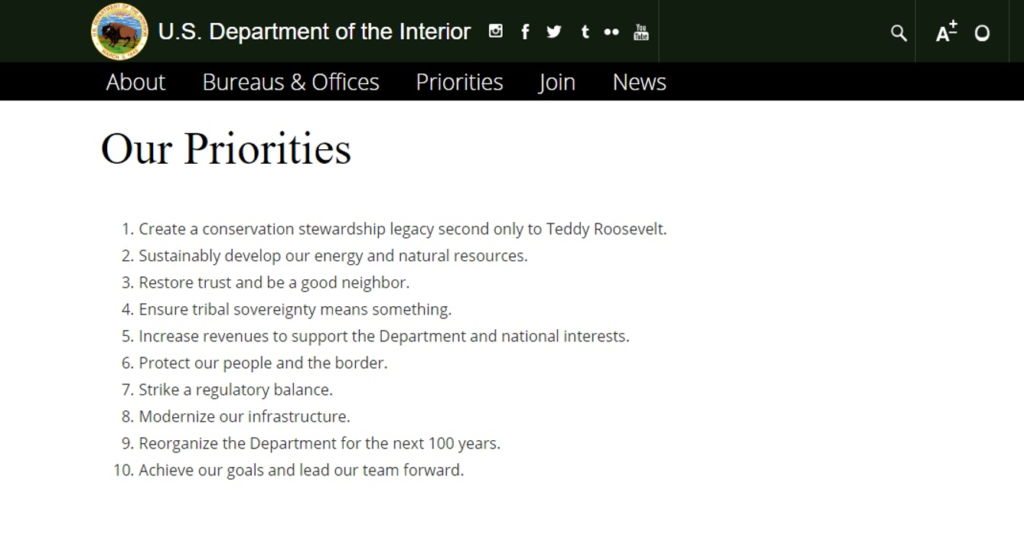

The lack of specificity is particularly notable on the “Our Priorities” webpage. This webpage also has fallen into neglect since its last update on August 8, 2018, when links were removed in the wake of the de-prioritization of “Climate Change”—and the removal of associated webpages—previously reported by EDGI. As the screenshot of the “Our Priorities” page below shows, several of the DOI’s supposed priorities are surprisingly absent of meaning. What, for example, does “Ensure tribal sovereignty means something” actually mean? What efforts are the DOI engaging in that support that priority? From the lack of information on the “Tribal Nations” page, there doesn’t appear to be much movement at all on that front. Similarly, whose goals are “our goals” in “Achieve our goals and lead our team forward?” This lack of specificity might be expected of a generic private company mission statement, but more should be expected of the DOI, which manages one-fifth of the United State’s land, public or private, and employs 70,000 employees and 280,000 volunteers at 2,400 locations, according to its “About” webpage.

In addition to the six priority areas listed in the navigation menu across the DOI website and the 10 priorities listed on the “Our Priorities” webpage, two other sets of visions and implied priorities can be found on DOI’s “About” webpage and in its Strategic Plan for Fiscal Years 2018–2022. Similar to the other two sets of priorities, the implied priorities in these vision and mission areas have congruence with each other, though no one list encompasses all of DOI’s declared “priorities.” On the “About” webpage, we find five vision statements:

- Promote energy security and critical minerals development

- Increase access to outdoor recreation opportunities for all Americans

- Enhance conservation stewardship

- Improve management of species and their habitats

- Uphold trust and related responsibilities

In the Strategic Plan however, we find six mission areas:

- Conserving Our Land and Water

- Generating Revenue and Utilizing Our Natural Resources

- Expanding Outdoor Recreation and Access

- Fulfilling Our Trust and Insular Responsibilities

- Protecting Our People and the Border

- Modernizing Our Organization and Infrastructure for the Next 100 Years

Bottom line

What shines through in this analysis is that the DOI currently lacks a clear and coherent set of organizing principles and consequent actions beyond the fervor with which the agency promotes resource extraction, now including hunting. This disheartening truth has been reflected in other posts by EDGI and throughout the media: the only real priorities of the DOI under the Trump Administration are commitments to intensify oil and gas extraction on public lands and the provision of extra consideration to a small segment of American society that happened to vote overwhelmingly for President Trump in 2016. It is the oil executives and avid hunters–a group in which Secretary Bernhardt claims membership–not the trail runners, river kayakers, bird watchers (sans bow or shotgun), or tribal members, whose interests matter most.