By Chris Sellers, Kelsey Breseman, Leif Fredrickson, EDGI

Abstract:

Throughout the history of U.S. environmental legislation, science has rightly served as our main touchstone for truths about threats to environmental and human health, but the Trump Administration has been slowly eroding its ability to do so. In this report, the first of a three-part survey of the many resultant challenges to the integrity of environmental science across our federal government, we show a substantive and intentional reduction of the influence of science and scientists on environmental policy-making over the last four years. Among the 95 rollbacks of environmental rules and regulations, the most sweeping take explicit aim at science’s current and future role in official decision-making. We tally the extent to which science advisory committees have been reconstructed, and to which EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler has favored input from industry and trade groups over those with staff scientists and more pro-regulatory NGOs (as evidenced by FOIA’d documents and interviews, as well as his calendar of meetings). We situate this clear de-prioritization of science-based regulation within a larger landscape of people and institutions pushing back, from federal scientists themselves to academic scientists and the courts.

Introduction:

Thirty years ago, hardly anyone knew or worried about the many environmental threats that today have become all too familiar. From the tiniest and most dangerous aerial particles, to watershed-scale run-off of pollutants, to greenhouse gases, Americans owe our current environmental awareness and protections not just to politics or laws, but to science. Without it, we’d be kept guessing about the sheer existence of many pollutants and other environmental influences on ourselves and our communities, as well as the dangers they pose to our ecology and health.

Good science is crucial to environmental governance; it’s how we understand lurking threats to our health, environments, and welfare. Without it, our government would be no more able to protect us than it was prior to the 1960s and 70s, when our modern environmental laws and agencies were first established. Without science, those powers our environmental agencies do exercise would be applied more arbitrarily, and more often on behalf of the politically strong and well-connected than the rest of us. That is where the Trump administration seems determined to take our country.

Three years in, the Trump administration’s continuing campaign against science in the federal government continues to chip away at science’s influence, capacity, and public face; that is, its internal as well as overall integrity. In so doing, the current administration has undermined vital environmental and health protections that science enables our government to provide. But science as an institution still exceeds the Trump administration’s grasp, both within the executive branch and without. The administration’s most sweeping efforts have met resistance from Congress and the courts, the quiet and continuous push of scientists who remain in the agencies, also the advocacy of scientists and other defenders of science beyond the government itself.

What follows is the first installment of a three-part survey of where these battle lines now stand, and how the Environmental Data and Governance Initiative has been following them.

Part 1: Targeting Scientific Influence on Policy

Since our environmental laws and agencies took their modern shape in the 1970s, they have relied upon the clarity and impartiality of scientific research to inform what, how, and how much to regulate. Scientific research clarifies what dangers are present, and which people, places, and ecosystems are in need of protection. Its findings enable officials and agencies to implement mandates to shield the health of humans and the environment in the full light of changing circumstances and knowledge. At the hands of the Trump administration, this vital reliance of environmental regulation on science is now imperiled.

Curbing Science’s Sway within Environmental Policies:

Among the 95 rollbacks of environmental regulations now underway, the most sweeping and ambitious share a common denominator: they seek to pare back the scope of scientific influence on our nation’s environmental policies.

The most glaring avatar remains the so-called “Strengthening Transparency in Regulatory Science” (STRS) rule. Pitched mainly as a move toward “transparency” that would halt EPA reliance on “secret” studies in favor of those that are more above-board and “reproducible,” it would instead reduce policymakers’ access to some of the most critical, policy-relevant health research. With well-documented origins among conservative politicians and tobacco industry tacticians, STRS targets the very kinds of science that have driven tighter standards for pollutants like particulates. The large-scale human-health investigations that have revealed health effects from long-term, low-level exposures to pollutants often use medical records that by law, must remain private. STRS would render research with data legally protected as “private” unusable in policy-making. Among the potential targets was the six-cities study by Harvard researchers from the 1990s, which provided strong and subsequently validated evidence that small (2.5 μm) air pollution particles like those produced by coal-fired power plants or cars that cause higher mortality and should be regulated. Protecting its data kept study participants safe and didn’t prevent other scientists from independently verifying or reproducing the results. EDGI’s public comment on the rule emphasized how the “transparency” it proposed and the reproducibility requirements it set are at odds with the best practices in this and other scientific fields. EPA’s latest iteration of this proposal, like an earlier version, does not improve accessibility of policy-relevant data or information. What it will do is enable officials to bypass and even retroactively repudiate the policy implications of our most revealing studies of environmental harm. An EPA without these scientific underpinnings cannot effectively regulate.

The 2019 revision of the Waters of the US Rule follows the same playbook. Not only does it exclude one-third of the nation’s streams previously covered under the Clean Water Act (CWA) in one fell swoop, it also peremptorily declares huge chunks of established scientific knowledge irrelevant to our nation’s efforts to keep our rivers and streams clean. When the Obama-era EPA expanded the CWA to cover those now-deregulated streams, it followed the obvious conclusions of a multitude stack of scientific studies that had been growing since the 1980s, demonstrating that contamination of small or impermanent bodies of water across a watershed contributes to downstream pollution. Moving to revoke this rule, Trump’s and Wheeler’s EPA ignored what a coalition of scientific societies termed “the best available science of connectivity” and regressed to a 1980s understanding of water pollution. Ironically, an EPA touting its commitment to “science transparency” also neglected to provide the public with scientific or environmental justifications for the change — EDGI’s public comment found that the EPA did not provide adequate information for the public to comment on the rule and showed that relevant resources had actually been removed a few months prior. Fourteen states have already launched a lawsuit against this rule change.

Revisions to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), rolled out early this year, also seek to curb the use or influence of science. They do so both indirectly and directly, by mandatory speed-up as well as circumscription of the environmental assessments NEPA requires of federally-sponsored projects and actions lying within its vast purview. Before NEPA’s passage in 1970, federally funded infrastructure projects like dams or highways displayed a deep neglect of environmental impacts. The 1970 law required project decision-makers to solicit scientific assessments of those impacts and take their findings into account in project decision-making (for more details and sources, see this annotation of speeches at the January 9, 2020, ceremony by EDGI’s Environmental History Action Collaborative). In mandating both scientific assessments and public hearings on what these assessments found, NEPA elevated into the decision-making process many others who had been voiceless: neighborhoods and endangered species whose futures are affected by development projects.

Given how much our scientific understanding of environmental dynamics has evolved over the last five decades, those environmental impacts assessed under NEPA have also had to be adapted. The growing understanding of watershed connectivity is just one strand of more “ecosystem-oriented” and regional approaches to water regulation that by the early 2000s gave rise to new NEPA models for restoration projects, for instance in the Everglades. The consolidating grasp of on-going trends in our climate, and the many associated changes up ahead, have posed a special challenge to NEPA’s front-end environmental assessments, leading the Obama administration in its last year to issue the first NEPA guidance for federal agencies on climate change. But the new Trump rules for NEPA overturn this guidance, curbing consideration of projects’ effects on climate and on all other “effects” that are “remote in time, geographically remote, or the product of a lengthy causal chain.” However clear and certain the science on “remote” and “lengthy” causation may be, this new version of NEPA legalistically rules its findings out, declaring these “should not be considered significant.” As EDGI’s Environmental History Action Collaborative noted in its annotation of speeches at the new rule’s rollout, the proposed changes to NEPA constitute a sweeping effort to limit the input of both science and the public on official decision-making–with troubling implications both for the durability of our infrastructure and for a livable climate.

Many other of this administration’s reconsiderations of environmental rules share this science-curbing thrust, from its rollbacks of regulations for methane and other greenhouse gases to its peremptory exclusion of “legacy uses” of asbestos and other toxics from its risk evaluations in implementing the revised Toxic Substances Control Act. Less public but also immensely impactful are the ways in which scientists themselves have been marginalized from agency decision-making or else pressured to conform.

Reconfiguring Advisory Boards:

Among the main targets of the Trump administration have been those many committees set up across the federal government through which professional scientists employed outside the government share their expertise and advice. From the start of the administration, tensions had been gathering between what its political appointees wanted to say and do and what advisory committees urged upon them. The result was Trump’s Executive Order in summer 2019 for all agencies to review their advisory committees and cut these by one-third. But far beyond this EO, scientists inside the federal government as well have seen their knowledge and advice sidelined in myriad ways, as political appointees pursue policymaking which conflicts with what professional scientists know and value.

While these science-curbing campaigns have recently received news coverage in the New York Times and the Washington Post, this coverage has less to say about what apparently drives them: the commitment of the executive branch’s political leadership to unleash “the regulated community” from the constraints imposed by environmental rules and laws. Political appointees intent mainly on serving the needs and demands of the regulated have sought to curb and minimize federal environmental oversight of large-scale and private enterprise whereever they can. Among the quickest and easiest avenues they’ve found for doing so is simply to clear the professional scientists themselves out of the way, thereby banishing the influence of those whose job it has long been to determine what needed regulating actually to protect Americans’ environments and health. Changes at the Environmental Protection Agency, ground zero of the Trump Administration’s offensive and the subject of an ongoing study by EDGI, offer a case in point.

Trump’s first EPA head, Scott Pruitt, touted economic growth, energy development, and job creation as nearly on a par with the agency’s missions of protecting public health and the environment. For the agency’s science advisory committees, that commitment led in 2017 to Pruitt’s exclusion from advisory committees of anyone receiving an EPA grant. Invoking a narrow “conflict of interest” principle that utterly neglected corporate paychecks or clientele, the restriction disqualified many prominent academic experts in relevant fields. At the same time, it opened influential doors to many more scientists employed or otherwise paid by private business as well as non-scientists.

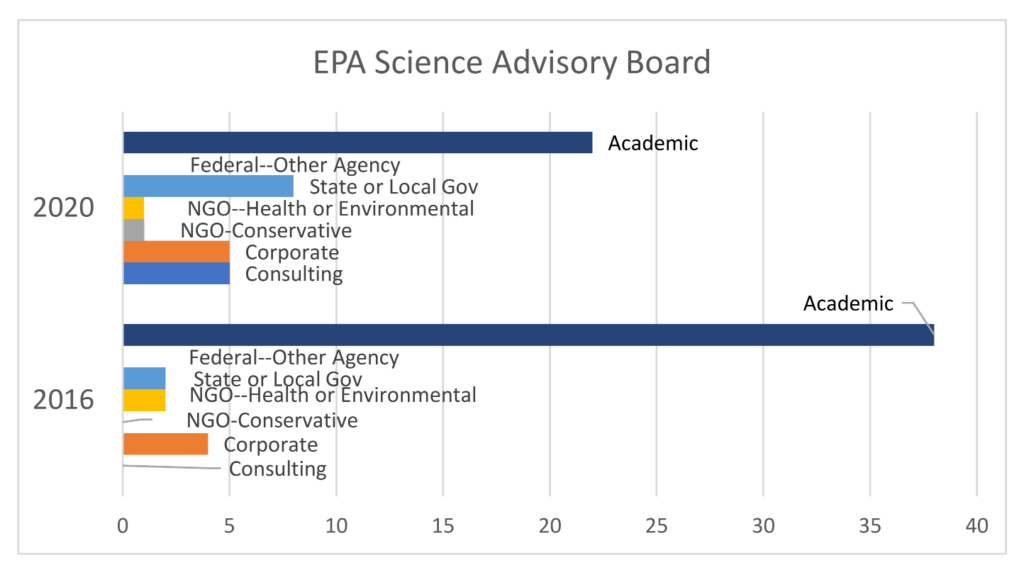

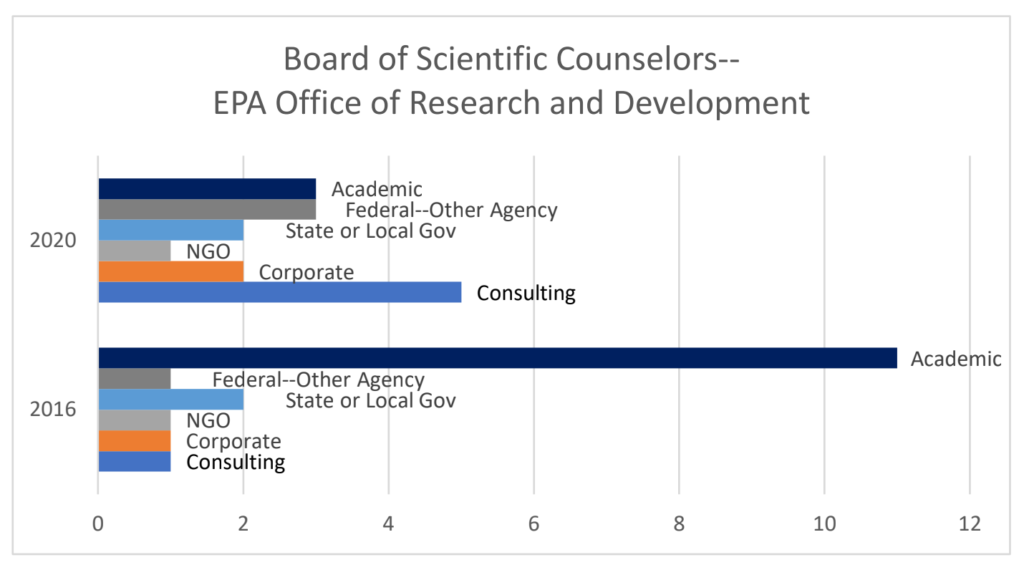

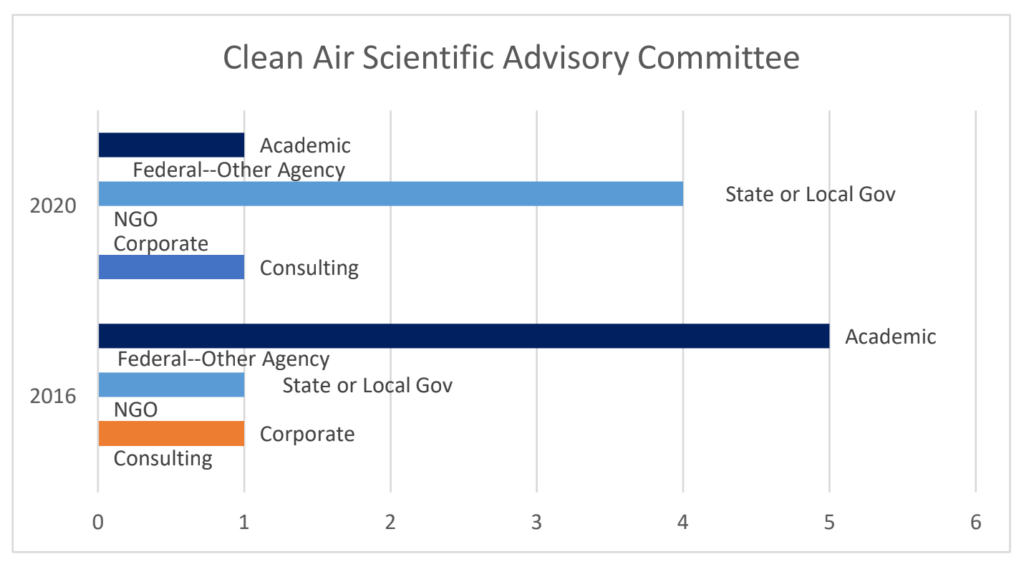

A year later, with Pruitt gone, his less confrontational replacement Andrew Wheeler stuck more to the traditional script about the agency’s mission. But the Pruitt-set trajectory still prevailed for review panels, as an established review panel for particulate air pollutants was disbanded and a planned panel for ozone cancelled. Restrictions on EPA grantees remained in place as Obama appointees’ terms on many of the committees ended, so the balance of EPA science advisory committees continued to shift away from academic scientists. Replacing those employed by universities or medical centers are those working not just for companies but for private consulting firms, as well as state and local officials almost entirely from “red states.” This displacement of academic scientists has been dramatic enough for EPA’s Science Advisory Board, the largest and highest-profile of these committees, where their share has been reduced from a whopping majority to around half. The shift has been even more pronounced on smaller yet still critical committees. The seven-member Clean Air Science Advisory Committee, now without assistance from subcommittees, remains in charge of ongoing reviews of most of the major air pollutants, but now has only a single academic scientists. On the review board for EPA Research and Development Office, the core part of the agency devoted to conducting or funding science, only three of the sixteen are academic scientists (see charts 1-3 below).

Charts 1-3: The Changing Composition of Key EPA Science Advisory Boards, 2016-2020

The share of academic scientists on all these boards plummeted. Those from consulting firms, (most of whose clientele were private businesses) and state and local governments (with all the newcomers from “red” states) increased their shares the fastest, though scientists directly employed by corporations also gained representatives. Sources: EPA website and EDGI-collected data

The EPA’s Bias of Access: Favoring Industry, Shunning (Its Own) Scientists

The Pruitt-era shunning of expertise and advice from the EPA’s own scientists first documented in EDGI’s EPA Under Siege (June 2017) continues under Wheeler. It has become accepted practice, a settled feature of the agency’s internal landscape. Our continuing interviews with recent agency retirees as well as current officials confirm the extent to which most key policy decisions are now made within the Office of the Administrator by political appointees. While Wheeler does go through more motions of consulting with career staff, many understand his listening as mainly for show, since so many policy changes eschewing their advice continue to gather momentum.

Our interviews with EPA employees have yielded much evidence about how Pruitt and his political appointees “circumvented this inclusive, deliberative process” by which career staff had long been involved in major policy decisions, whether on rule-makings or research funding. “Skirting the whole long-established process,” the new political leadership “just made the decision,” eschewing the regular meetings of representatives from different parts of the agency that had happened under his predecessor, Gina McCarthy. As career staff were left in the dark about how key decisions were being made, “rumor and innuendo” proliferated; for instance, that a “hallway conversation” between Pruitt and Bill Wehrum (his appointee to head EPA’s air office) set their strategy for replacing the Clean Power plan.

Since replacing Pruitt, Wheeler’s approach to career staff, while less overtly hostile, strikes many with whom we’ve spoken as mainly cosmetic. “Wheeler is a great masquerader, and so he puts on this façade of being the anti-Pruitt, but it’s really no different….maybe people are sitting around the periphery, but what they say is not considered and there’s no real dialogue.” The political leadership is still “making decisions based on no science or economic analysis.” While some of them are “very capable attorneys,” they “do what they want to do and write what they want to do and they do that in a fairly closed environment…they brought in a handful of…special assistants, probably most of them with law degrees as well. They just write stuff. They don’t involve people much in it. The general counsel’s office gets involved a bit and those people are under a lot of stress, the career people are under a lot of stress.”

Instead of scientists, the Administrator’s office is listening not just to its own lawyers but the “regulated community”: the companies releasing health-harming emissions that the EPA was set up to protect the American public against. From the internal documents EDGI has secured under the Freedom of Information Act, their doors and ears remain open to these companies, which they casually term the “stakeholders” of regulatory work, with little or no reference to any communities their pollution might affect. When representatives of Bayer’s CropLife division wanted to make a case against using epidemiological studies in pesticide evaluations, Nancy Beck, political appointee running the Office of Chemical Safety, met with and listened to them (FOIA records; Beck calendar). When a coalition of petroleum trade groups sought to protest “methodological inadequacies” — as they put it — in how the agency had handled “unconventional oil and gas wastes” — that is, from fracking — Pruitt chief legal counsel Sarah Greenwalt opened her door to hear them out (FOIA records).

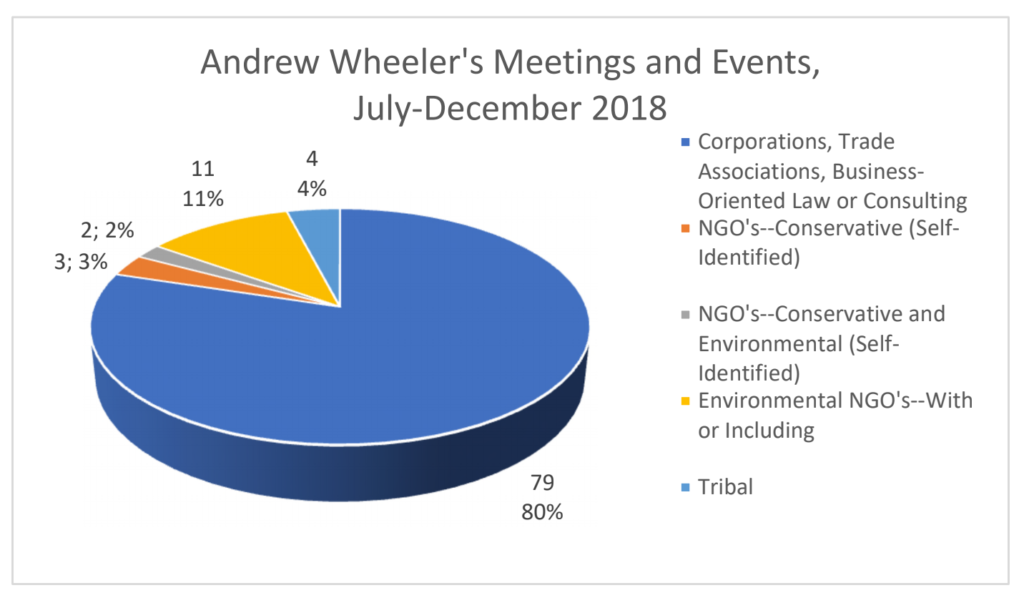

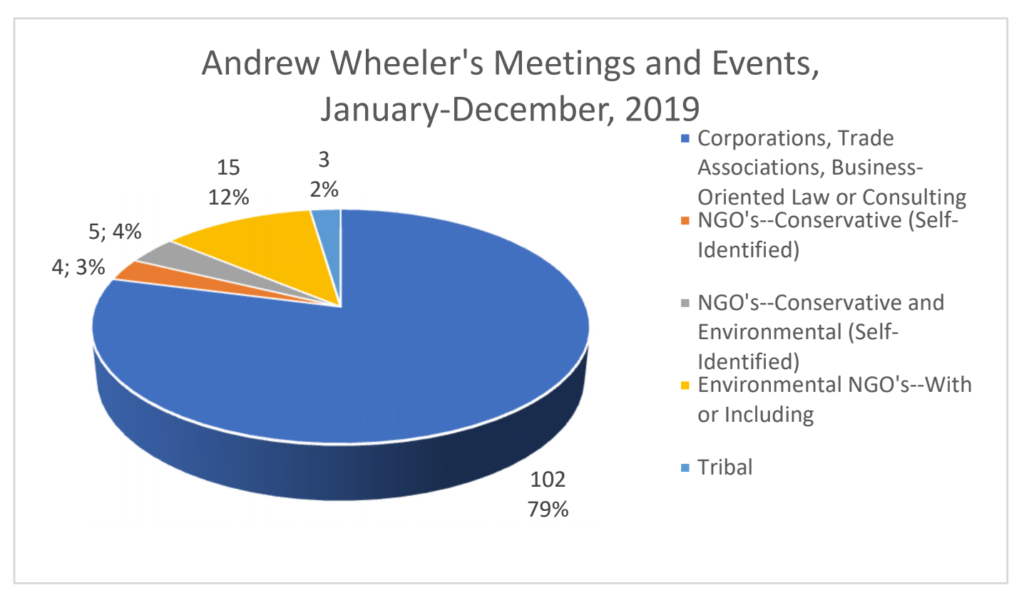

The lopsided receptiveness to industry and trade groups that began under Scott Pruitt has only mildly abated under Wheeler, even as coverage by the media has greatly fallen off from 2017 when the New York Times carefully documented Pruitt’s dramatic shift from his predecessor Gina McCarthy, who entertained a more balanced schedule. This past December before the holidays, Wheeler had speaking engagements with the National Association of Manufacturers and the Executive Management Council meeting, and appeared at the Wall Street Journal’s CEO Council Reception. He found time to meet or call representatives of some nine companies and a consulting firm, as well as the American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers. But he scheduled only a single half-hour meeting with any environmental or industry-independent scientific group, the Health Effects Institute. Since promoted to Acting Administrator in July of 2018 through 2019, Andrew Wheeler has met or spoken four times with the National Association of Manufacturers and five times with the National Association of Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers. As with Pruitt, energy companies appear especially favored by Wheeler’s attention. So do conservative and climate-science skeptical policy stalwarts heavily funded by this sector, such as the Heartland Institute (two visits) and the Heritage Foundation (two visits).

Wheeler has met 33 times with environmental groups in his first 18 months as EPA administrator — about one-fifth of the 181 times he has met with corporations, trade associations, or business-oriented firms over the same period. Many of the environmental groups privileged to meet with the Environmental Protection Agency’s administrator are explicitly “conservative” in their orientation. The American Conservation Coalition, whose website header calls for “environmental action…limited-government solutions,” was granted four visits. Others environmental groups on Wheeler’s schedule have little or no regulatory agenda, notably those favoring recycling such as 4Ocean, which sells products made from plastics washing up on beaches to “end the ocean plastics crisis,” Rock and Wrap It Up, which delivers food waste to needy pantries and soup kitchens, and the “America Recycles Day” leadership. No doubt recycling has a part to play in America’s environmental strategies, yet its promotion should not be the main public focus of the leader of our nation’s premiere environmental agency, tasked with regulating emissions that doom communities to cancer, render water sources undrinkable, and corrode the livability of our global climate. Over the last year and a half, only a handful of Wheelers’ chosen interlocutors have had more or less critical emphases on environmental regulatory policy, including the Bipartisan Policy Center, Mom’s Clean Air Force, and the Union of Concerned Scientists.

Charts 4 and 5: Andrew Wheeler Hears Out Companies Far More Than Environmental Advocates

Favored audiences with distinct interests from outside of government, as indicated by number of appointments with different kinds of groups and organizations from July, 2018, the month he was appointed Acting Administrator, through 2019. Sources: Andrew Wheeler calendar and EDGI-collected data

Pushing Back?

This extreme bias of access to EPA’s political leadership has undoubtedly bolstered its push to lighten regulations on business. With its chosen interlocutors mostly only providing supportive arguments for the many new legal restrictions and rollbacks, the administration seems to be effectively remaking environmental policy-making at the EPA and other agencies in ways that curtail the input of science and scientists. But while the administration can thereby boast of many deregulatory accomplishments over the short to medium run, the very circling of wagons that has speeded these “achievements” also means that their longer-run success is far from guaranteed.

Career scientists and data- and policy experts whose voices are now going unheeded face a difficult time both professionally and personally. Morale remains low. In the words of one EPA employee: “If you have any integrity, any passion for the work you’re doing and… if you’re studying the pesticide impacts of women’s thyroid and you’ve been studying that for 15 years and we decided we don’t need to do that anymore…how are you supposed to feel?” Some, like biologist Matthew Davis, have left, in his case after he was asked to provide scientific justifications for overturning tightened standards on mercury that he himself had helped write. While Davis walked away from the “darker dirtier future” his bosses seemed to want, into a job with the League of Conservation Voters, others remaining at the agency work to keep their own sense of the agency’s mission alive. Hunkered down, deliberately trying to keep off the radar screen of political appointees, they plow ahead on their investigations, data collection, analyses, enforcement actions, and other oversight— many of them hopeful that the November elections will bring a reversal of the agency’s direction.

Despite this administration’s concerted campaign against the influence of science on environmental policy and the allied “deep state” theories of the right wing — of a civil service somehow devoted to undermining the law, property rights, and democracy — there are signs that the dismantlement of environmental protections may only proceed so far. Despite pressure from conservative groups, the Trump administration has not (yet) moved to overturn the endangerment finding, the 2009 determination by the Obama era EPA that greenhouse gases were threats to public health that fell within the scope of the Clean Air Act. As the New York Times recently reported, the sustained effort to loosen the fuel efficiency rules put in place under Obama has run up against inconvenient facts furnished by economists, namely that the rollback would actually cost consumers more. That costs of a rule rollback may outweigh its benefits to the economy do not bode well for the inevitable judicial challenges. Already, anti-science policies passed by Wheeler’s EPA and other federal environmental agencies have faced skepticism and pushback in many courtrooms. Illustratively, a November judicial decision struck down the Wheeler EPA’s exclusion of “legacy uses” from its risk assessments for toxic chemicals like asbestos and lead. The three-judge panel’s decision, requiring that leaks or spills of stored toxics also be taken into account, exemplified how fundamental science remains in courts seeking to distinguish “reasonable” policies from those warped by legalistic pro-industry line-drawing.

Perhaps the strongest indicator yet of the resilience of the scientific basis for environmental protections despite current challenges is the failure of Trump-era appointees to turn the EPA’s Science Advisory Board (SAB) into a rubber-stamp political tool. Despite now being chaired by a Trump appointee — Michael Honeycutt, from the Texas Council on Environmental Quality — and despite its recomposed balance away from academics and toward industry and red-state agency experts, at the end of December the SAB publicized its own strongly worded critiques of major policy changes pushed by Wheeler and his staff. Honeycutt’s board found that the Science Transparency, Waters of the US, Clean Car standards, and Toxics rule reconsiderations were all overly neglectful of existing science. As Honeycutt put it, “We’re all scientists…dedicated to trying to get the science right. We take this very seriously.”

But while around half of this SAB were still academic scientists, the proceedings of another agency science panel with only one remaining academic, the Clean Air Science Advisory Committee, told another story. By early last year, its chair Tony Cox, from a corporate consulting firm, had joined with member Steven Packham of Utah’s environmental agency to question the long-established scientific consensus that tiny particulates in soot caused premature death, rooted in studies like Six-Cities. And late last year they joined with two of the other seven to recommend against tightening the particulate standard, going against the scientific assessments both of EPA staff and of an independent panel that convened itself, after the agency’s own particulates expert panel was disbanded. Opposing the new CASAC majority, only the committee’s remaining academic, a pulmonologist, as well as a scientist/regulatory official from Georgia thought the science favored a tighter standard.

Yet the roadblocks facing the administration’s efforts to reduce science’s influence on environmental policy remain formidable. This month, a federal judge for the first time rejected EPA’s policy of restricting those with EPA grants from advisory panel membership, citing multiple failures of the agency to provide the “reasoned explanation” required by the Administrative Procedures Act. Here and elsewhere, current leadership in our environmental agencies may have been misled by the communicative loops it has closed around its own policy-making, also by a shallow, legalistic understanding of how the environmental version of the regulatory state has long worked. In other words, it appears to have inadequately grappled with the utter dependence of our environmental laws on science. Nor has it fully reckoned with the trust earned by our scientific institutions and the responsibility felt by scientists themselves to uphold that trust.

Nevertheless, three years into the Trump administration, science’s role in federal environmental policy stands at or near a crossroads. Scientific practices and institutions still retain considerable sway at the EPA and other federal agencies, thanks to a capacity and legitimacy consolidated over time and backed up by bulwarks of the academy and the courts. But while our environmental agencies and laws have faced and weathered many past challenges, never have they encountered such a coordinated and sustained campaign targeting the science that underpins so much of their work. For now, the commitments of career staff and institutions such as the SAB, the courts, and Congress are fending off the sharpest edges of the on-slaught. Yet it is not clear how long they can hold out. Four of seven judges on the Supreme Court now seem eager to overturn a doctrine of judicial deference to federal agencies that has long undergirded regulatory reliance on science. If this reversal does succeed, then environmental regulation itself might turn out all too much like ecological systems, passing its tipping point and flipping into a new normal in which sound science can no longer be mustered to inform policy.

Note: This is the first of a three-part series. Later installments over the coming weeks will cover the shearing of scientific capacity and the veiling of the public faces of federal environmental science.

For press inquiries contact edgi.comms@gmail.com