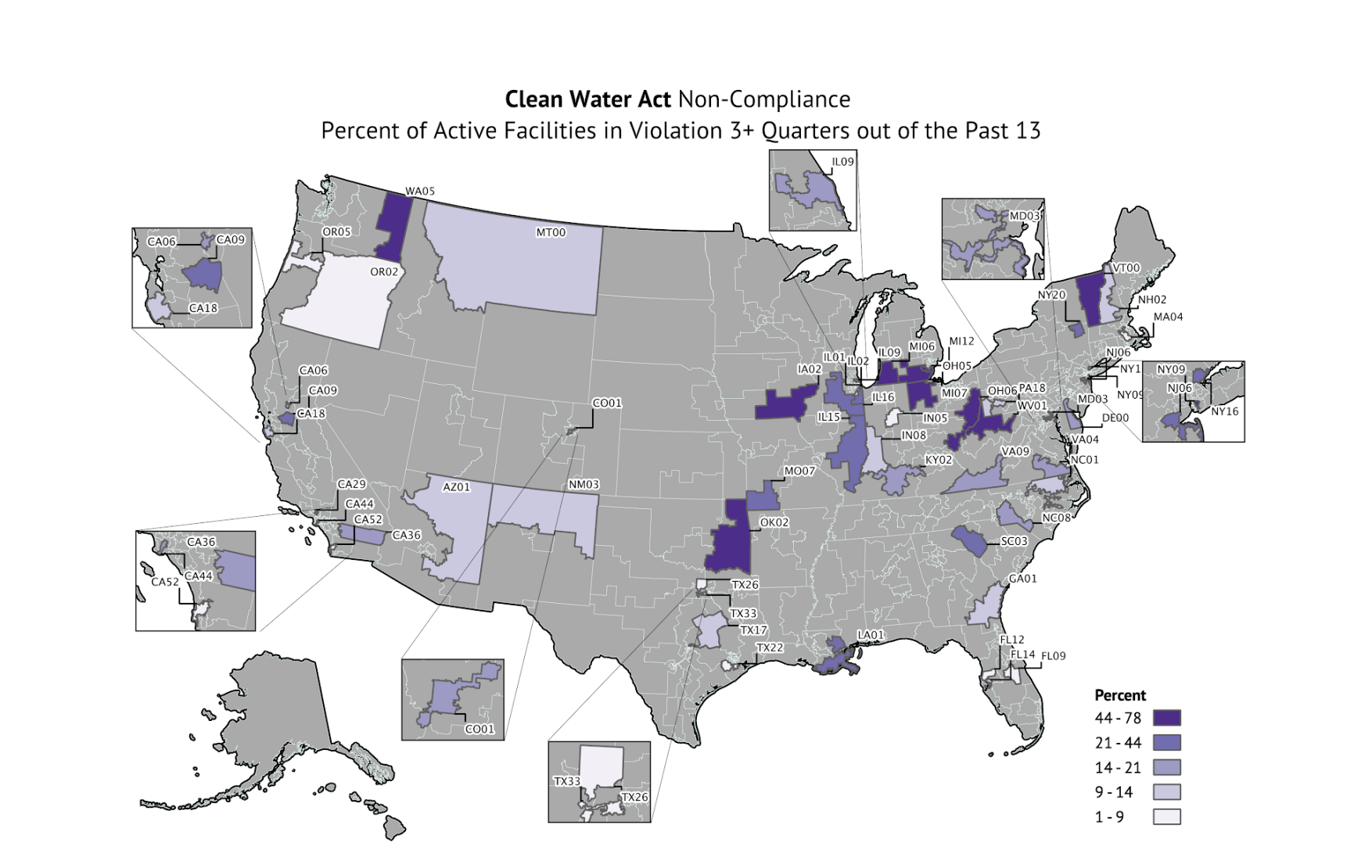

Figure from Democratizing Data report. Percentage of active facilities regulated by the CWA that were out of compliance for nine months (three quarters) or more out of the three years and three months (thirteen quarters) prior to October 2020. Source: EPA, Enforcement and Compliance History Online.

This essay was originally published in Science for the People magazine Volume 23 No. 2 – A People’s Green New Deal. Please use the following citation: Nost, E., S. Wylie, K. Breseman, G. Gehrke, C. Sellers, L. Vera, L. Richter, B. Mansfield, and Environmental Data & Governance Initiative (EDGI). A Green New Deal for Environmental Data. Science for the People. 23(2): 72-75.

By Eric Nost, Sara Wylie, Kelsey Breseman, Gretchen Gehrke, Chris Sellers, Lourdes Vera, Lauren Richter, Becky Mansfield, Environmental Data & Governance Initiative

The Green New Deal (GND) promises a remaking of much of the US’s infrastructure while centering climate justice. Through what it calls “transparent and inclusive consultation, collaboration, and partnership with frontline and vulnerable communities”, the GND would guarantee universal access to clean water, clean up hazardous waste sites, and identify and remove other pollution sources.1 While much debate over the GND centers around project costs, far less attention is paid to ensuring transparency and inclusivity in both goal-setting and tracking progress. How will we know which polluters are abiding by stricter controls and which need cleaning up? Will this work remain mainly in the hands of a technocracy, or will community science be welcomed by regulators? We propose a set of policies that support these aims through better data practice: a Green New Deal for environmental data.

The Opacity of “Open Data”

Right now, although some data is technically available to local communities to answer these questions, it is obscure and flawed. Open data portals provided by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) such as EPA’s Enforcement and Compliance History Online (ECHO) are typically context-scarce pass-throughs for chemical data provided by facilities under regulation – valuable in theory, but meaningless to most people.2 Under the current system, dual burdens fall on the most vulnerable communities: the lion’s share of hazardous risks and the responsibility to identify subsequent health problems. This requires communities to seek out, scrutinize, and self-teach about industrial emissions and then fight for enforcement actions or more protective policies. We believe that the GND must shift all of these burdens off of communities at risk and remake basic infrastructure for pollution reporting, enforcement, and chemical regulation and engineering. GND data must be accessible and focus on measuring material improvements in the lived experiences of vulnerable communities. It will need to knit together grassroots and big data systems in what we have dubbed “environmental data justice”.3

Over the past few decades, data has become a crucial but limited and vulnerable public resource for frontline communities to track and organize action against polluting facilities. Over this time, the US federal government has made several environmental pollution databases more widely available, including EPA’s Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) (1998), ECHO (2010), and the National Institutes of Health’s ToxMap (2004) (recently shuttered).4 But because this data is self-reported by polluters and lacks adequate documentation, many communities have had to collect their own. For example, a campaign led by Tonawanda, NY residents and the Clean Air Coalition of Western New York (CACWNY) alerted elected officials of a coke (refined fossil fuel) manufacturer’s releases of benzene, a carcinogen.5 The activists gathered their own air samples using low-cost tools to show benzene levels were 75 times higher than the EPA standard and beyond what the company itself had reported.6 After government agents raided the facility, its environmental control manager was charged under the criminal provisions of the Clean Air Act and sent to prison. However, not every frontline community’s data is welcomed by authorities and, while the activists’ efforts are admirable, a lack of data should not have been their problem to solve. Under a GND, we need bedrock federal legislation to ensure adequate and accessible environmental information.

When industry sequesters environmental data, monitoring and enforcement become inadequate and environmental health problems can arise from unchecked emissions. Confidential business information shields many chemicals – such as those used for fracking – from government or public oversight.7 Industry studies that reveal known threats to environmental health are also often kept secret. For example, data connecting polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and human birth defects was not disclosed by 3M or DuPont to EPA until a lawsuit against the company in 1999.8 In contrast, the EPA operates in the dark: it is required by law to approve new chemicals for use within just 90 days of receiving an application, data submissions by chemical companies are optional, and the burden of proof to demonstrate harm is placed on agency staff.9 Recently, the federal government has taken advantage of COVID-19 to limit EPA enforcement and allow polluters to report measurements taken after unmet deadlines for testing air monitors.10 We must address these practices of manipulating, withholding, and failing to collect data that make protecting public environmental health impossible.

The federal government’s own existing environmental data infrastructures are fragmented and partial, making oversight impossible. Reporting standards are facility- rather than community-centric, failing to account for the cumulative impacts of many facilities in the same area. There were 982,000 active oil and gas wells in the U.S. in 2018, all exempt from Clean Air Act reporting requirements because each well’s emissions do not meet existing criteria for major sources of hazardous air pollutants.11 Additionally, not only is much of the data in EPA’s TRI industry-reported, it can be based on estimates and models rather than actual on-the-ground monitoring of emissions.12 Effective monitoring of thousands of emitters is beyond the capacity of any single federal or state agency, and requires a new plan.

How Can the GND Facilitate Environmental Data Justice?

The GND could allocate federal resources to support data compilation that is sensitive to place- and situation-based needs. New data infrastructures might build on nascent efforts such as EPA’s advisory council’s 2016 recommendation to incorporate citizen science data like CACWNY’s throughout the agency and agency efforts to develop low-cost air sensors.13 These infrastructures could be further supported by academic, agency, and community collaborations to create responsive research networks similar to those developed around infectious diseases. Pairing environmental health data with other public health data could help researchers identify communities where environmental health risks increase vulnerability to diseases such as COVID-19.14

Major improvements in reporting need to be accompanied by a push of similar magnitude for data accessibility. The ECHO database is one of the best tools available for learning about environmental pollution. It displays facility-specific data on emissions, compliance, and enforcement under the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, and several other programs. And yet, in its current design, the data portal leaves an inexpert public bewildered rather than informed: large numeric tables accompanied by unfamiliar acronyms and occasional legalese can confuse a community’s understanding of what is happening in nearby facilities (figure 1). A justice-centered approach would be more proactive, informing surrounding neighborhoods of major local polluters or permit violations and providing summaries and reference values to orient users.

Towards a Green New Deal for Environmental Data

The GND’s overhaul of the toxic fossil fuel economy must contend with the data infrastructures that enable it to persist. We believe revamped data practices can – in combination with new regulations, programs, and funds – provide leverage for systemic change. We envision the GND enabling community production and uptake of environmental information, repealing data secrecy laws, and mandating that polluters adopt advanced platforms for emissions monitoring.

A Green New Deal for environmental data must include both legal requirements for reporting real-time industrial emissions – rather than post-hoc estimates – and the development of data tools that alert interested communities and agencies when regulatory thresholds are exceeded. Federal funding should be allocated to hire, train, and equip members of frontline communities to collaborate with EPA and state officials on monitoring and enforcement (along the lines of federal Office of Economic Opportunity programs of the late 1960s and early 70s). Additionally, environmental monitoring and analysis should be incorporated into existing public institutions such as public schools, libraries and universities. Improvements to the review of new chemicals under the Toxic Substances Control Act are vital to require polluters to prove that their products are safe – similar to processes followed by the Food and Drug Administration – and EPA should expand the number of unregulated chemicals it periodically monitors. The GND should reinforce existing limits on what data industry can claim as “confidential business information” and make it readily available to federal and state regulatory staff, while ending non-disclosure agreements that prevent information on environmental contamination from circulating into the public domain.

Regardless of the outcome of the 2020 election, we must demand these kinds of reform. They are important steps to making existing regulations far more protective of environmental and human health. However, to more deeply address the chronic, systemic problem of ubiquitous contamination with hazardous chemicals, a GND must change how we conceptualize and measure harm. Existing regulations give industries permission to pollute based on outdated toxicological models that overlook low-dose cumulative exposures, exposure science that aims to only control human exposures rather than protect the ecosystems that humans depend upon, and fate and transport modelling that still support dilution as a pollution solution. The science and data on which our regulations are based need a deep overhaul to produce metrics that go beyond cost-benefit analysis to instead evaluate impacts on collective human and environmental health for all populations.

- H.R. Res. 109, 1st Session (116th Congress), https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-resolution/109/text#H61778C683B874B1188DCF69E3CD558C4. [↩]

- For instance, facilities regulated under the Clean Water Act through the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES), submit their data directly to an EPA database that the ECHO portal draws on. See: https://echo.epa.gov/tools/data-downloads/icis-npdes-dmr-summary. [↩]

- “Environmental Data Justice,” Environmental Data & Governance Initiative, accessed March 4, 2020, https://envirodatagov.org/environmental-data-justice/; On community right-to-know, see for instance, Fortun, Kim, Lindsay Poirier, Alli Morgan, Brandon Costelloe-Kuehn, and Mike Fortun. “Pushback: Critical Data Designers and Pollution Politics.” Big Data & Society 3, no. 2 (December 2016). [↩]

- “Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) Program”, United States Environmental Protection Agency, last modified February 12, 2020, https://www.epa.gov/toxics-release-inventory-tri-program; “Enforcement and Compliance History Online”, United States Environmental Protection Agency, last modified March 3, 2020, https://echo.epa.gov/; Chris Sellers and EDGI, “Goodbye to ToxMap–and Our Environmental Right-to-Know”, Environmental Data & Governance Initiative, last modified December 11, 2019, https://envirodatagov.org/goodbye-to-toxmap-and-our-environmental-right-to-know/; Kim Fortun. “Environmental Information Systems as Appropriate Technology.” Design Issues 20, no. 3 (2004): 54–65. The Trump administration has also demonstrated the vulnerability of such information to censorship, outright erasure, and disinvestment: “Website Monitoring”, Environmental Data & Governance Initiative, accessed March 4, 2020, https://envirodatagov.org/website-monitoring/; Danny Vinik, “What happened to Trump’s war on data?”, Politico, July 25, 2017, https://www.politico.com/agenda/story/2017/07/25/what-happened-trump-war-data-000481. [↩]

- “Tonawanda”, Clean Air Coalition of Western New York, accessed April 12, 2020 https://www.cacwny.org/campaigns/tonawanda/ [↩]

- “THE POWER OF A FEW: CITIZENS USE SCIENCE TO STOP ILLEGAL POLLUTER.” Citizen Science Community Resources. Accessed April 12, 2020 https://csresources.org/our-history [↩]

- Sara Wylie, Fractivism: Corporate Bodies and Chemical Bonds (Duke University Press, 2018). [↩]

- Lauren Richter, Alissa Cordner, and Phil Brown, “Non-Stick Science: Sixty Years of Research and (In)Action on Fluorinated Compounds,” Social Studies of Science 48, no. 5 (2018): 691-714. [↩]

- “Reviewing New Chemicals under the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA)”, United States Environmental Protection Agency, last modified December 19, 2019, https://www.epa.gov/reviewing-new-chemicals-under-toxic-substances-control-act-tsca/epas-review-process-new-chemicals; Lauren Richter, Alissa Cordner, and Phil Brown, “Producing Ignorance Through Environmental Regulatory Structure: The Case of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)” Forthcoming; “Toxic Substances Control Act, 5 USC Ch. 53: TOXIC SUBSTANCES CONTROL”, accessed June 25, 2020, https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title15/chapter53&edition=prelim. [↩]

- Kelsey Breseman, Eric Nost, Gretchen Gehrke, Chris Sellers, Marcy Beck, Lourdes Vera, and EDGI, “EPA’s COVID-19 Leniency is a Free Pass to Pollute,” accessed June 25, 2020, https://envirodatagov.org/epas-covid-19-leniency-is-a-free-pass-to-pollute/; US EPA, “Continuous Emission Monitoring; Quality-Assurance Requirements During the COVID-19 National Emergency,” accessed June 25, 2020, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/04/22/2020-08581/continuous-emission-monitoring-quality-assurance-requirements-during-the-covid-19-national-emergency. [↩]

- William J. Brady, “Hydraulic Fracturing Regulation in the United States: The Laissez-Faire Approach of the Federal Government and Varying State Regulations,” accessed March 4, 2020, https://www.law.du.edu/documents/faculty-highlights/Intersol-2012-HydroFracking.pdf; “U.S. Oil and Natural Gas Wells by Production Rate”, U.S. Energy Information Administration, last modified December 20, 2019, https://www.eia.gov/petroleum/wells/. [↩]

- Utah Department of Environmental Quality, “Frequently Asked Questions – Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) Program,” accessed June 25, 2020, https://deq.utah.gov/environmental-response-and-remediation/cercla-comprehensive-environmental-response-compensation-and-liability-act/frequently-asked-questionstoxic-release-inventory-tri-program. [↩]

- “Air Sensor Toolbox”, United States Environmental Protection Agency, last modified February 13, 2020, https://www.epa.gov/air-sensor-toolbox; National Advisory Council for Environmental Policy and Technology (NACEPT), “Environmental Protection Belongs to the Public: A Vision for Citizen Science at EPA,” United States Environmental Protection Agency, December, 2016, https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-12/documents/nacept_cs_report_final_508_0.pdf. [↩]

- Sharon Lerner, “EPA IS JAMMING THROUGH ROLLBACKS THAT COULD INCREASE CORONAVIRUS DEATHS,” The Intercept. Accessed April 12, 2020. https://theintercept.com/2020/03/31/epa-regulations-air-pollution-coronavirus/ [↩]