A summary by Garance Malivel & the EDJ Working Group

On February 28th, 2019, the Environmental Data Justice (EDJ) Working Group hosted its first online public event, starting off a series of conversations at the intersection of data justice and environmental justice work. It brought grassroots projects, activists, academics, and students together to learn from and inspire one another. Aiming at developing guiding principles and practices for Environmental Data Justice, the collective discussion explored the following questions: Where, how, by whom and for whom are environmental data collected, stored, and used? How can we address and redress the socio-economic and technological redlining that condition where communities live and what infrastructures and services they are surrounded by? What tools do we need to support community digital literacy, and work toward more equitable, transparent, and inclusive models of environmental data governance?

Gathering on Zoom without major technical hiccups—hats off to the facilitators Kevin Nguyen and Damion Donaldson, and to all those who joined our backstage rehearsals!—about seventy attendees engaged in a two-hour uplifting forum. The animation of the chat box in which everyone was invited to share questions and comments, made up for the oddity of speaking to an invisible and silent audience.

After the event coordinator, Damion Donaldson, introduced participants to the features of the virtual conference room, moderator Lourdes Vera outlined the event’s questions. Building on the legacy of Environmental Justice to address the disproportionate harms faced by racially, socially and/or economically marginalized communities, the vision of EDJ is also grounded in the developing movement for Data and Digital Justice. As such EDJ seeks to critically analyze and rethink the political and technical structures that generate environmental inequalities, as well as produce the data that informs policy. In this framework, the “environment” is broadly defined, and includes both “natural” and built dwelling places, but also food accessibility and state or corporate violence as they affect communities’ livelihood. The event was organized into two panels, where people presented their lessons and achievements from their own EDJ related projects.

Panel 1: Data Justice and Sovereignty Principles

From community-led internet infrastructures in Detroit, to an international network enacting “Indigenous Data Sovereignty,” and reflections on Google’s efforts to develop a smart city in Toronto, this first panel questioned how and why data are extracted from people and environments. Additionally, panelists discussed ways in which community control of over their data could be increased through “Data Sovereignty”: community ownership and active engagement in directing data gathering, distribution and analysis.

Kristyn Sonnenberg: Detroit Community Technology Project

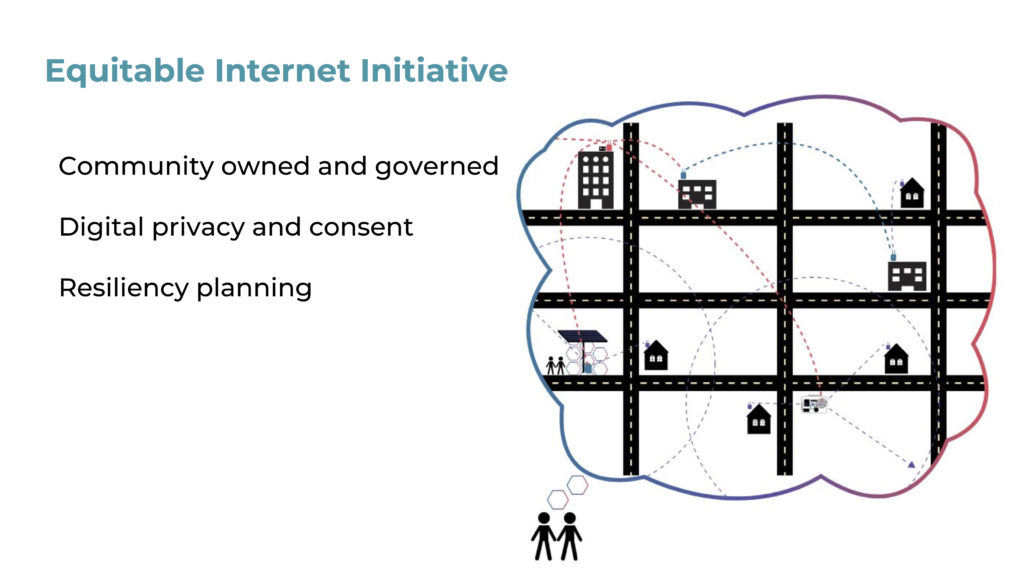

Kristyn Sonnenberg presented some of the projects by the Detroit Community Technology Project (DCTP). DCTP’s work fosters community technology access, infrastructure, and education. Growing out of Allied Media Projects’ inspiring work to mobilize media and technology for social change, DCTP builds on the Detroit Digital Justice Principles, which emphasize notions of access, participation, common ownership, and healthy communities. From “Data DiscoTech” events engaging youth in learning about the ins and outs of data practices, to the publication of zines and handbooks to share organizational resources, DCTP cheerfully demystifies technology and promotes a community-oriented vision of communication infrastructures. The group has recently engaged Detroit’s residents in a series of discussions to reflect on the city’s Project Green Light—a public-private initiative to provide local businesses with surveillance cameras that stream live to the Police Department through high-speed connections. As a counterpoint to the use of technology for “security” and policing, the group has developed an Equitable Internet Initiative that increases community Internet access through shared connections in underserved neighborhoods. Digital Stewards are locally trained to bring their communities online, and the organization is working toward the creation of neighborhood Resiliency Networks to be used in emergency situations.

Desi Rodriguez-Lonebear: U.S. Indigenous Data Sovereignty Network

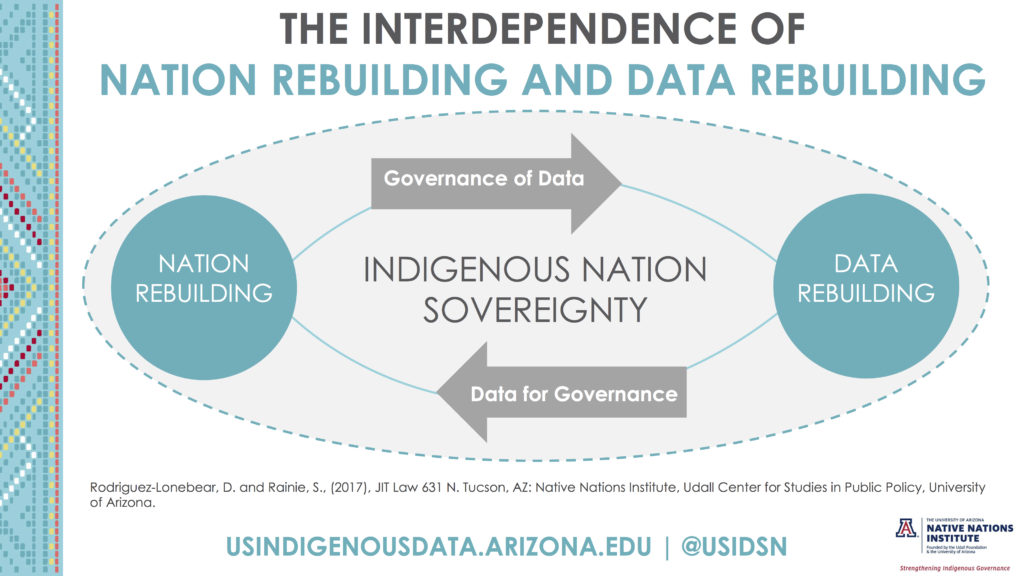

Co-founder of the U.S. Indigenous Data Sovereignty Network, Desi Rodriguez-Lonebear similarly highlighted the importance of building community capacity and redistributive infrastructures. Indigenous peoples, Desi emphasized, have always been “data experts”—a quality she called being “relentlessly empirical.” What we think of now as research and data acquisition were critical to Indigenous survival before and after European contact. Yet colonization processes have not only jeopardized Indigenous nations’ political and territorial sovereignty, but also their knowledge infrastructures and data sovereignty. “Data decolonization,” then, aims to reduce Indigenous dependency on settler structures and infrastructures. In this paradigm, Indigenous data characterizing, for instance, a community’s environment, health, culture, political or commercial entities, are not collected by settlers for themselves, but by Indigenous peoples, whether for themselves or the settler state. “Governance of data”, Desi pointed out, is about developing Indigenous control of “data for governance”. On the path to Indigenous data sovereignty, building support mechanisms and reciprocal relationships between tribal institutions, governments, corporations, and researchers, are key elements for data decolonization.

Nasma Ahmed: Digital Justice Lab

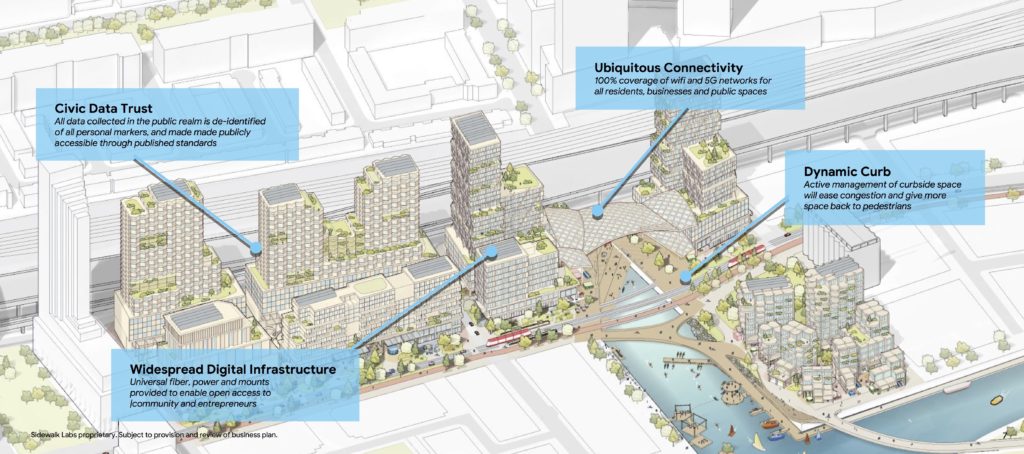

Concluding the first panel, Nasma Ahmed, head of the Digital Justice Lab in Toronto, talked about the organization’s role in activating critical discussions around Sidewalk Labs’ “smart city” project, that would extend on the city’s eastern waterfront. Owned by Alphabet—Google’s parent company that oversees the tech giant’s subsidiaries—Sidewalk Toronto has the mandate to “accelerate urban innovation” and reimagine cities “from the internet up”. Echoing Desi’s work towards Indigenous data ownership, Nasma pointed out the risks of massive data collection and commodification inherent to Sidewalk’s experimental project. Lacking a clear data governance proposal, and having neglected to make its consultation processes more inclusive, Sidewalk Toronto has faced growing opposition and calls for the project’s cancellation. Through a series of Alternative Urban Futures Evening Talks, the Digital Justice Lab has provided a framework to reassess the idea of a “smart city”. It advocates for otherwise “connected” communities, and promotes the development of common data ownership.

Panel 2: Learning from Environmental Data Justice Projects

The speakers of the second panel shared transformative data practices for Environmental Justice work. We were inspired by their stories of successful community-led research projects to ban toxic industries, to build participatory data experiences to make industrial pollution visible, and to use data visualization to push back against gentrification-driven evictions.

Olga Bautista: Southeast Environmental Taskforce

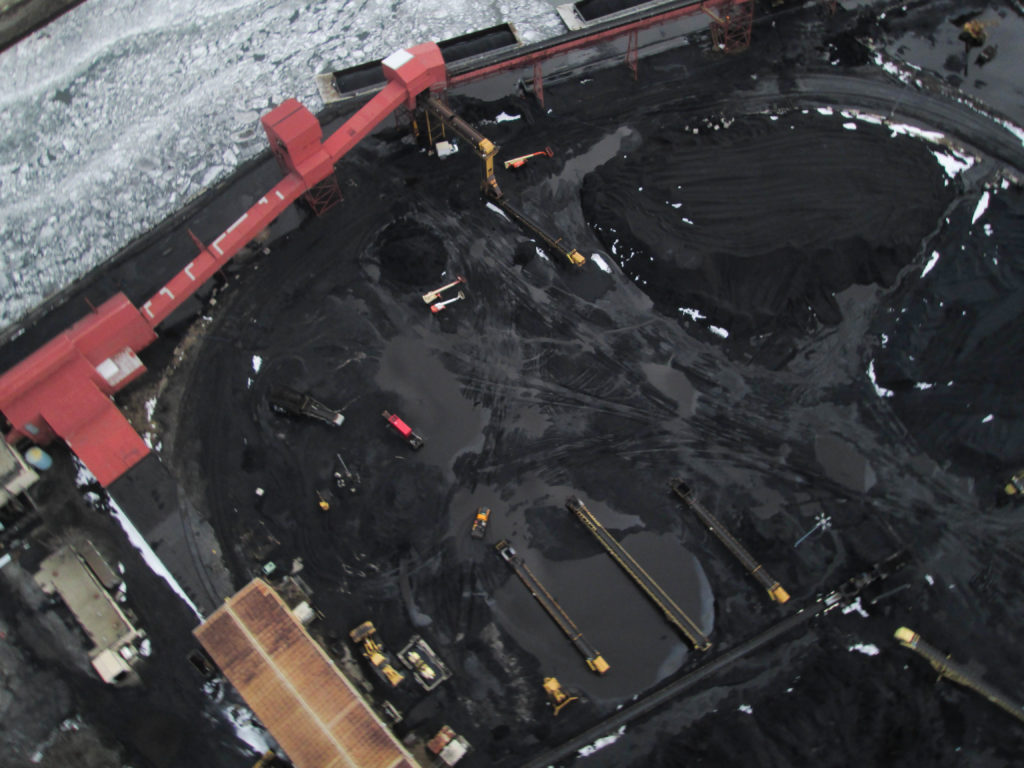

Olga Bautista from the Southeast Environmental Taskforce (SETF), a nonprofit that promotes environmental education and pollution prevention for southeastern Chicago residents, talked about her work organizing community resistance to petcoke storage in the 10th ward of the city. The picture that opened her presentation shows a landscape with a black dusty cloud in the background. After the shut-down of the steel industry in the 1980s, a facility was reconverted into a large open-air storage for petcoke, a solid fuel produced from tar sands refining. A source of fine dust (PM10), petcoke can be associated with heart and lung diseases which, in the “Windy City,” became a major health concern for surrounding communities. Mobilizing local residents through social media campaigns and door-knocking, Olga and other members of what would become the Southeast Side Coalition to Ban Petcoke, collaborated with Sara Wylie (EDGI), Chris Walley (MIT) and PublicLab, to produce their own aerial maps of the petcoke storage site, using helium balloons equipped with digital cameras. After 3 years of mobilization, two EPA notices of violation, and the installation of air monitors on the facility’s fenceline, new city regulations were adopted and the storage company (owned by the Koch Brothers) was forced to enclose or eliminate the black dusty piles. The subsequent removal of petcoke was a victory for surrounding communities. Yet it would bring about another battle, when air monitoring campaigns additionally revealed dangerous levels of manganese in the air—another byproduct of the steel-making plants that surround Olga’s community. With a wealth of experience mobilizing against petcoke, residents are still today battling unsafe levels of manganese in their neighborhood.

GreenRoots’ ECO Youth Crew

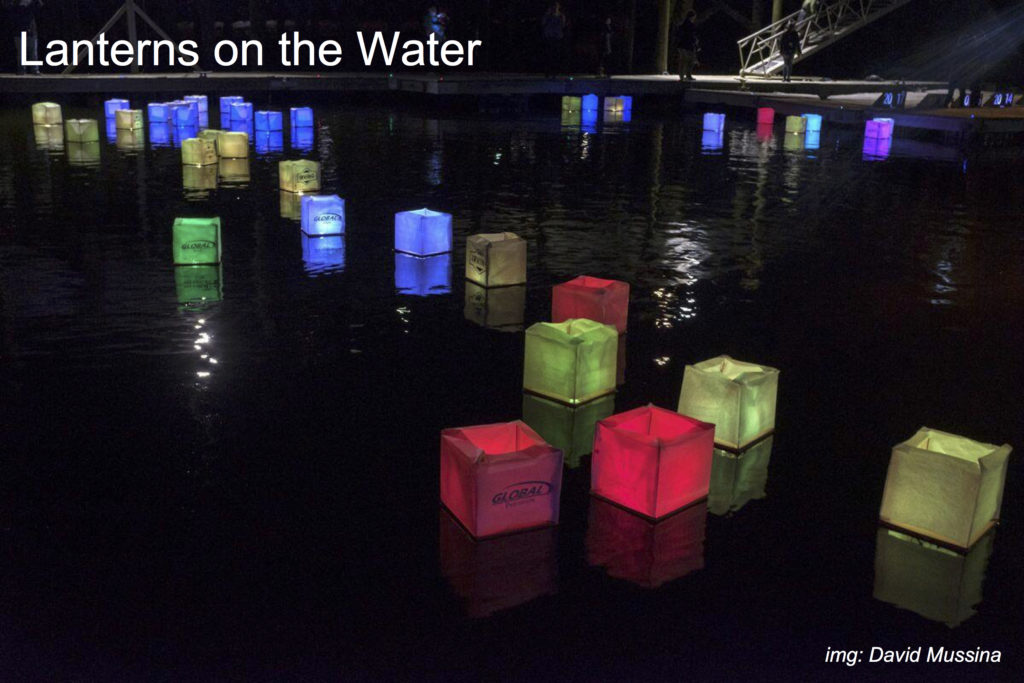

Similarly engaged in informing local communities about the environmental health impacts of industrial contamination, six members of GreenRoots’ ECO Youth Crew (Jasmin Lainez, Jary Perez, Alanis Muñoz, Bryan Hernandez, Shakaya Moore Perkins, and Katherine Zelaya) collectively presented their work around the Chelsea Creek. Chelsea is a small city just north of Boston whose entire waterfront is zoned for water-based industries by the State. Regional power plants, oil and gas storage tanks, metal recycling facilities, and a large open-air road salt distribution center line both sides of the creek. The diverse community—composed of 73% of ethnic minorities, mostly Latinx, and where 24% of residents live below the poverty line—shoulders much of the industrial burden for the region. In collaboration with Laura Perovich (MIT Media Lab) and Sara Wylie (Northeastern University), the ECO team used the EPA’s ECHO (Enforcement and Compliance History Online) database to aggregate data on 76 Clean Water Act violations performed between 2013 and 2017 by oil storage facilities; these violations resulted in the release of chemicals such as Benzene, BTEX, and naphthalene in the Chelsea Creek. ECO organized a “data performance” to make the toxic discharges visible through floating lanterns, whose colors each corresponded to a specific type of chemical. The event was followed by a community meeting to discuss the environmental justice concerns brought to light throughout the project. It is documented on the website http://datalanterns.com, where other communities can find information about how to host their own data lantern event. With the decline in Clean Water Act enforcement at the EPA, documented in EDGI’s recent report, ECO hopes performances such as these can help make violations publicly visible. In Chelsea, the data performance has resulted in a series of follow-up meetings with local oil storage companies.

Erin McElroy: Anti-Eviction Mapping Project

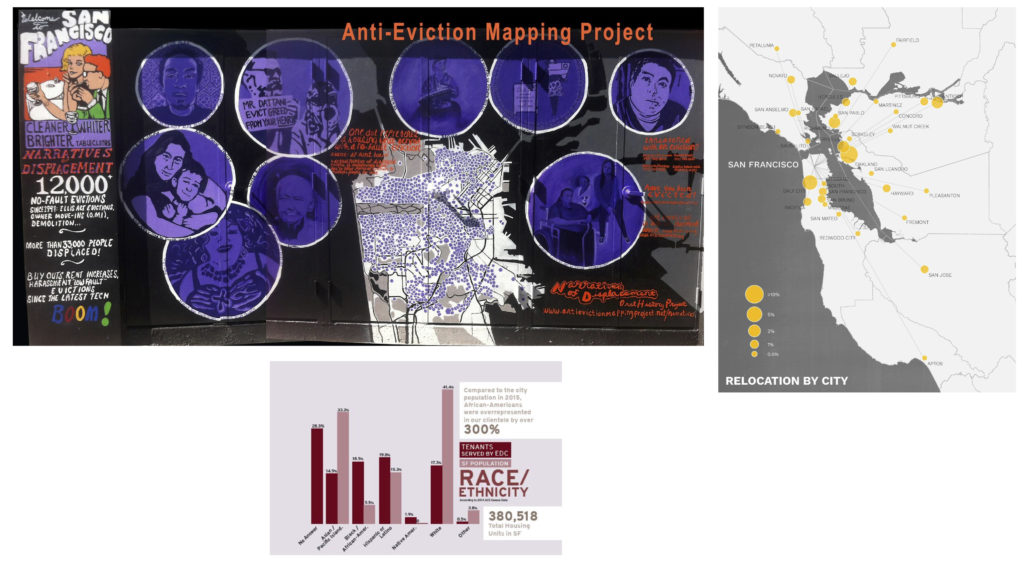

Closing the panel, Erin McElroy, cofounder of the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project (AEMP), likewise emphasized the power of visual and creative approaches to inform communities and demonstrate the socio-environmental prejudice they face. Erin talked about gentrification in the San Francisco Bay area, driven by the settlement of young, affluent dwellers employed in Silicon Valley. Using critical cartography, AEMP not only maps rampant rates of eviction that have affected the area since the late 1990s, but also their overlap with locations of corporate bus stops across the city, rent increases, and proliferation of year-round Airbnb rentals. The neo-colonial dimension of these urban and demographic transformations are illustrated by the overrepresentation of Black and Latinx residents among displaced communities. The experience and resistance of these communities are also documented through digital projections and storytelling. A mural in San Francisco’s Mission district features a map of no-fault evictions in the neighborhood since 1997, as well as the portrait of eight residents, the stories of whom can be heard by the passerby through a phone number associated to the mural. Erin insisted on the importance of grounding such initiatives on community work, and of consolidating existing networks in collaboration with other local organizations. Efforts solely based on online presence and a globalizing approach to social injustices, would by contrast run the risk of missing the mark and failing to effectively support communities.

Open Discussion

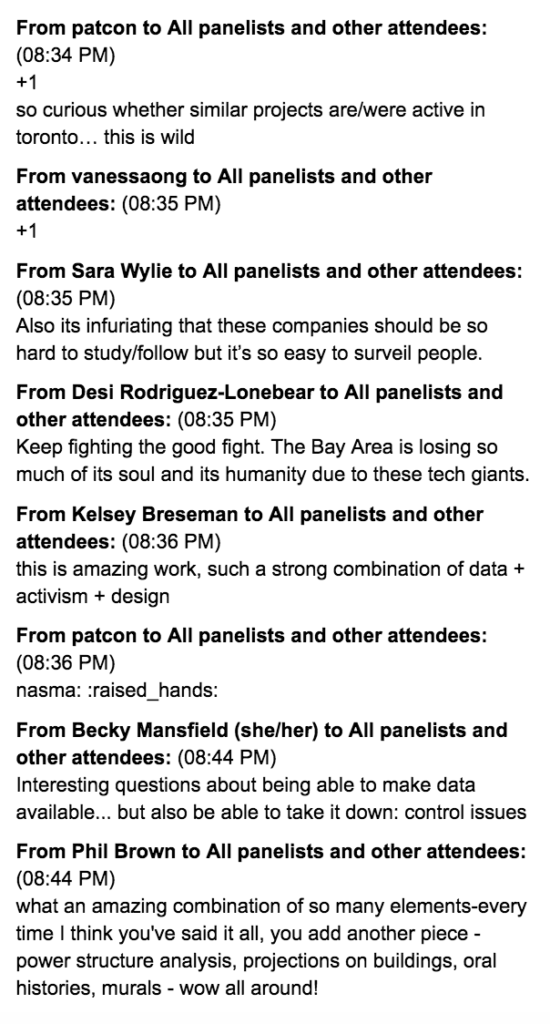

Zoom chat box

A number of shared values and practices emerged across the diversity of projects presented over the two panels. Deeply interdisciplinary in nature, they mobilize a set of methods from scientific research, activism, art and design to critically analyze how power dynamics translate into physical and digital infrastructures. Building on intersectional approaches to environmental harm, a number of these campaigns have also developed visual strategies as a way to effectively inform and collaborate with communities. Beyond evidencing environmental risks and injustices, they bring critical questions into public debates and public spaces.

Some new lines of thought were outlined throughout the event, inspired both by the panel discussions and questions shared by the participants:

– Moving beyond the extractive approaches that have often prevailed in scientific research and data practices, how do we develop and maintain reciprocal efforts to create more equitable models of environmental data governance?

– How do we address consent and attend to communities’ privacy concerns while engaging in public outreach?

– How can we better sustain advocacy work, which more often than not relies on volunteered energy and time?

– How can we avoid representing concerned communities as “damaged” or dispossessed, and instead highlight and strengthen their capacity and resiliency?

Along these lines, the EDJ Working Group undertook to collectively compile a syllabus to outline key principles, readings, toolkits, methods, and projects that could further inspire and support environmental data justice work. An upcoming series of demos and presentations is also intended to expand on the experiences and lessons shared over this first online public event.

We are welcoming anyone willing to join the conversation! Please feel free to join the EDJ Slack to get informed about our next meetings, or reach out to us at edj(at)envirodatagov.org. We look forward to hearing from you.