As a student, did you ever ask yourself, What is the point of all this? When education feels disconnected from practical implications, it can be hard to see the sense in studying for another exam or writing another paper. Making a difference in society might not even enter consideration. Now, imagine trading in some of those exams and papers for an active role in public-interest research: You wouldn’t just learn the facts of your subject, you’d create new knowledge to share with the world. Over the past semester, EDGI partnered with an undergraduate course to offer just that kind of trade-in. For students, the course was an opportunity to directly engage with the environmental information they studied and with their federal government. For us, it was an opportunity to support information literacy in new ways. This expansion of EDGI’s public research work into the classroom shores up the foundations of our work for the longer term and highlights emerging modes of participatory pedagogy.

In June 2017, EDGI’s Web Monitoring Team was circulating an email to recruit new volunteer analysts. At the same time, Lizz Ultee, a climate science PhD candidate at the University of Michigan, was designing a new climate literacy course. The course, “Knowing Climate Change”, would use community-based learning pedagogy to situate students directly in the civic context of their coursework, but the perfect partner organization had thus far been elusive. Among other challenges, the scheduling of the course for the Winter semester–winter in Michigan–made any work outdoors much less feasible. Fortunately, the Web Monitoring Team’s email landed in Lizz’s inbox at just the right time to spark our partnership with the course.

Imagine trading in some of those exams and papers for an active role in public-interest research: You wouldn’t just learn the facts of your subject, you’d create new knowledge to share with the world.

After meeting by chance at a book club in Ann Arbor, Lizz and Justin Schell, who works with several EDGI working groups and directs the Shapiro Design Lab at the University of Michigan Library, agreed to talk further about how the class could get involved with EDGI. One of the possibilities discussed at our first meeting was to bring students in as web monitoring analysts. Most analysts spend 10-20 hours per week on their web monitoring work, but we envisioned that splitting responsibilities among a large cohort of students could reduce the weekly workload into line with a standard three-credit-hour course. Following this initial conversation, we brought the idea to the larger Web Monitoring Team to work out what students would monitor and how their observations would integrate into the overall workflows and logistics of the web monitoring project.

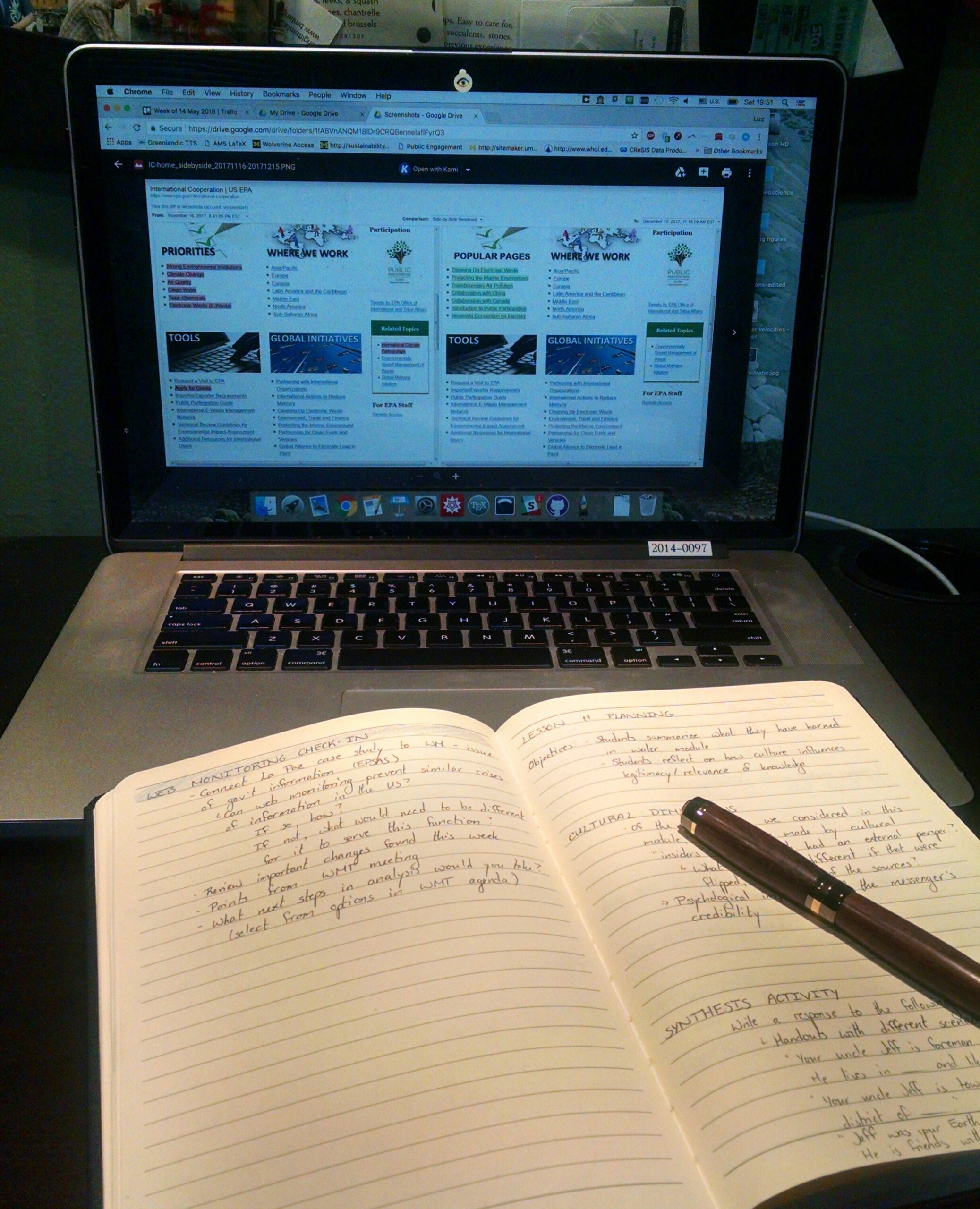

Students in “Knowing Climate Change” analysed information about climate change science and societal impacts from academic and popular sources in addition to the government websites they monitored. Given that web monitoring was only part of students’ workload for the course, we were careful to balance demands on their time with truly useful work for the team. Contributing directly to the project was important, as it offered a more authentic research experience. We agreed that the students would analyse aggregated changes to web pages from domains that had been captured over the course of a year by our software but hadn’t yet been examined by members of the Web Monitoring Team. This approach encouraged deeper knowledge of the pages within each domain while increasing the chances that students would find something important or interesting. We also determined that Lizz would collect students’ important changes to report to the Web Monitoring Team, rather than insisting students attend every weekly meeting. Easing the time-specific expectation to report changes at the team meeting allowed students more flexibility to fit web monitoring to their individual schedules. In keeping with the collaborative spirit of EDGI, though, students were always invited to attend relevant meetings and from time to time they did choose to do so.

Working through EDGI’s web monitoring process gave students firsthand experience of critically evaluating government-produced information. In class discussions, students described their sense of surprise–and sometimes outrage–at the webpage changes they were finding and might otherwise never notice. Summarizing her experience with EDGI, student Tyler Underwood writes:

“Prior to taking this class and working with EDGI I had absolutely no idea how fluid the availability and content of knowledge is online. … [Public] viewpoints stem from what is readily available for people who have questions and are quickly searching the web to make a stance on a topic. If the EPA doesn’t even show up on the first page of a search about climate change, then it is easy to see our government’s stance on the topic….I have found that arguing with people who do not believe in climate change is pretty difficult, but educating them on how their thoughts may be influenced by the easily available information is much more effective.”

The information literacy skills students developed as web monitoring analysts helped them bring a critical eye to academic topics as well. When presented with a new article, video, or image, students began to ask: Who made this? Why was it created or written this way? What other perspectives would I need to form a complete picture of the situation?

Despite the decidedly technical nature of the work, clicking through Google Sheets and scouring the Internet Archive Wayback Machine to pinpoint when changes were made, students found in it an enhanced spirit of civic engagement. They were glad to be “doing something”, actively participating in American civic life and paying attention to their government. One student reflected, “Through website monitoring, I felt that I was successfully able to be involved in climate change conversation with a hands-on approach. It was a powerful feeling to be able to contribute to the preservation of climate change information and knowledge. I think that our EDGI work throughout the semester was successful in creating a body of knowledge on climate change action and government accountability.”

Engagement with the class benefited EDGI’s web monitoring team in several ways- it expanded the team’s reach and made important contributions to its body of work. It served as a useful test of current web monitoring processes and laid the foundation for future involvement with student groups.

“Through website monitoring, I felt that I was successfully able to be involved in climate change conversation with a hands-on approach. It was a powerful feeling to be able to contribute to the preservation of climate change information and knowledge. I think that our EDGI work throughout the semester was successful in creating a body of knowledge on climate change action and government accountability.” – Student Reflection

The class documented over 2000 changes across 13 web domains, 180 of which were deemed important. They investigated web pages under the EPA, NASA, and NOAA, areas the EDGI team had been unable to cover because of limited bandwidth. Some of the pages, particularly the state-level EPA domains, were of strategic interest across the broader EDGI community and indeed the class investigations proved fruitful. Some of the most concerning changes uncovered were removals of informational documents about climate change, which are being investigated by the WM team and could be developed into a future report.

Monitoring tens of thousands of federal agency websites is a big task. EDGI’s web monitoring team employs several custom processes involving a fair amount of manual work, and onboarding new volunteers is challenging. One of the key long-term benefits of the course is the work Lizz and Justin did to build an easy-to-use onboarding process which enabled the students to get up and running in a matter of weeks.

The overall structure established for the class to engage in the web monitoring work was well thought out, and well documented. The biggest challenge we found in developing the framework was molding the required web monitoring processes to meet the constraints of the class environment. Our first step was to mirror the workflow and data collection in a separate and controlled environment. Then, much discussion went into how the students would interact with the software platform. The streamlined, longitudinal structure we developed will frame future engagements between the WM team and universities, helping to amplify EDGI’s core mission and serve as a recruiting ground for new volunteers.

Ultimately, public environmental information is most accessible when those who would interact with it understand how to do so fruitfully. EDGI’s support for information literacy in the classroom supports this broad conception of accessibility and government accountability, and it lays foundations for an informed and active citizenry. We look forward to exploring yet more possibilities for students and instructors to co-create knowledge with us.

If you are interested in working with EDGI for your own course, we encourage you to contact us at EnviroDGI@protonmail.com. An example syllabus and other course materials are available for sharing, and we would be happy to discuss new ideas for course engagement.